If, as Oscar Wilde once said, “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life,” then the art of film has a lot to answer for when it comes to the perpetuation of gender stereotypes. Thanks to researchers in the Allen School’s Natural Language Processing research group, we now have a way to measure the sometimes subtle biases in how men and women are portrayed on the big screen — and increase our understanding of how language shapes our perception of gender roles.

A team that includes Ph.D. students Ari Holtzman, Hannah Rashkin and Maarten Sap, bachelor’s alumna Marcella Cindy Prasetio, and professor Yejin Choi analyzed nearly 800 movie scripts across multiple genres and found that male characters tend to be vested with higher levels of authority and control over their own destinies than their female counterparts. The researchers applied connotation frames — a method for understanding the connotations associated with different verbs — to assess characters’ level of power and agency through their actions and speech. Even after controlling for the disparity in the number of roles, quantity of dialogue, and screen time assigned to male versus female characters, the team found that males consistently scored higher across all genres.

“What we found was that men systematically have more power and agency in the film script universe,” Holtzman said in a UW News release.

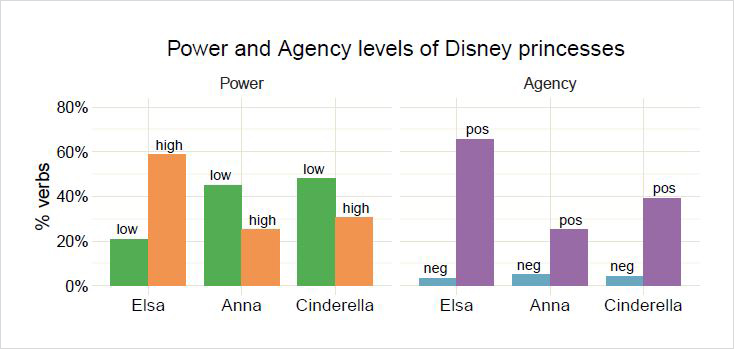

In addition to analyzing scripts, the team applied its framework to the plot summaries of several popular Disney princess movies. What they found was that, when it came to power and agency, several of Disney’s most beloved characters are not exactly living a fairy tale. This includes Anna, one of the main protagonists in the popular 2013 film, “Frozen.” While her sister, Elsa, was portrayed as being in command of her own destiny, Anna possessed much less control and often had to rely on the assistance of a man — showing that when it comes to gender stereotypes, not much has changed in the Disney universe in over half a century.

“Anna is actually portrayed with the same low levels of power and agency as Cinderella, which is a movie that came out more than 60 years ago,” said Sap, lead author of the paper that describes the team’s results. “That’s a pretty sad finding.”

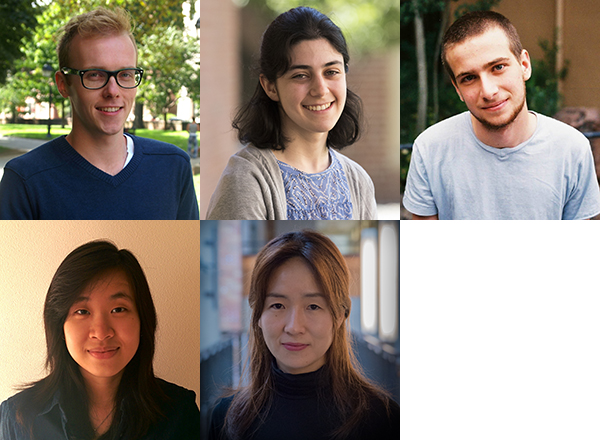

The research team (clockwise from top left): Maarten Sap, Hannah Rashkin, Ari Holtzman, Yejin Choi, and Marcella Cindy Prasetio

The project built upon previous work by Choi, Rashkin, and former Allen School postdoc Sameer Singh that defined connotation frames for analyzing how a writer’s choice of verb implies certain attitudes and relationships between subjects — revealing how seemingly objective statements by an author can influence readers’ judgment about people and events. Originally conceived as a potential tool for analyzing subtle biases in online media, the framework was extended to reveal how the verbs used by and in relation to movie characters suggest power and influence along gender lines.

The researchers’ approach goes beyond a well-known method for measuring gender bias in known as the Bechdel Test. That test has gained traction over the last decade as a proxy for identifying films that offer a more robust portrayal of women that is about more than their relationships with men. Whereas the Bechdel Test stipulates that a movie must have at least two characters who are women and who speak to each other about topics other than a man, the Allen School’s framework provides a more nuanced analysis of the differences in how men and women are portrayed on the big screen.

Interestingly, the team discovered the discrepancy is not necessarily down to male writers perpetuating a deeply ingrained gender imbalance — it carries over into films scripted by female writers and overseen by female casting directors, too.

“Even when women play a significant role in shaping a film, implicit gender biases are still there in the script,” Rashkin noted.

While the team focused on characters playing on the big screen, the same method could help people recognize the subtle biases conveyed in books, plays, and more.

“We believe it will help to have this diagnostic tool that can tell writers how much power they are implicitly giving to women versus men,” Choi said, noting that these subtle biases are “deeply integrated in our language.” Eventually, the team hopes to broaden its tool to offer potential solutions, such as suggestions for ways to rephrase passages of text.

Choi and her colleagues created an online database that enables researchers and members of the public to explore their findings for hundreds of popular films. Try out the interactive tool here, and read the UW News release here. Listen to Rashkin and Sap explain their work on an episode of KUOW’s The Record here.

The team presented its findings in September at the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2017) held in Copenhagen, Denmark.