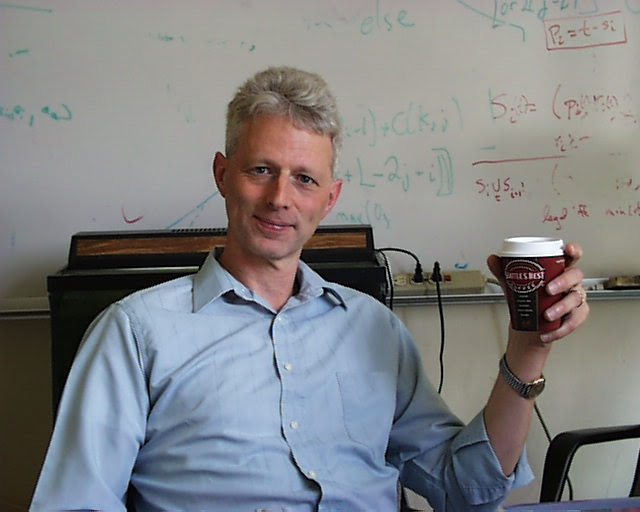

Allen School professor Martin Tompa, an early and leading expert in computational molecular biology and a beloved mentor to undergraduate and graduate students, retired from the Allen School at the end of June. Tompa’s long and distinguished career spans an array of computer science research, including computational complexity, algorithms, and computational molecular biology. And then, of course, there’s his mastery of Schnapsen — the 300+ year old card game with an avid following in Europe and, thanks to Tompa, in the halls of the Allen School.

As an undergraduate at Harvard University in the early 70s, Tompa wanted to study computer science. It wasn’t offered as a major at Harvard at the time so he graduated in 1974 with a degree in applied mathematics. He still took every opportunity he could to take classes in computing and conducted undergraduate research with Thomas Cheatham, an early pioneer of extensible programming languages. As a computer science Ph.D. student at the University of Toronto, Tompa’s research focused on theoretical computer science, work that he continued at the University of Washington after he was hired onto the faculty in 1978.

“I first met Martin when, in the fall of 1977, I was on sabbatical leave at the University of Toronto where he was a graduate student. I was thrilled when he decided to come to UW when he finished up his Ph.D. in 1978,” Richard Ladner, Allen School professor emeritus, said. “Through all these years he has been a valued colleague and friend. I especially appreciated Martin at faculty meetings where he would be a stickler to make sure our decision processes were fair and unbiased. Martin is also a wonderful game player in social games like contract bridge and his favorite, Schnapsen.”

In 1984, Tompa won an inaugural Presidential Young Investigator Award for his work in computing foundations. The next year, Tompa and his wife Anne McTiernan and two daughters left Seattle for New York, where McTiernan earned her medical degree. From 1985 to 1989, Tompa was on the staff of the IBM Research Division at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center and became manager of its Theory of Computation Group.

Four years after their departure for the east coast, McTiernan was offered a residency position at UW Medicine and they were thrilled to return to Seattle. Tompa was welcomed back to the CSE department’s Theory of Computation research group. He switched gears in 1998 to study computational molecular biology.

“I enjoyed working in both theoretical computer science and computational molecular biology,” Tompa said. “There’s something wonderful about theoretical computer science — mathematics is so clean and proving things is wonderful. Molecular biology has been really exciting over the last few decades and it was exciting to learn about it. It was great fun to work with biologists and write programs to help with their analyses.”

Tompa was interested in the structure of DNA and learning the functions of its various parts. He worked on comparative sequence analysis, comparing the DNA sequences of multiple organisms to see what they had in common and where they differ.

“It was a lot of work to switch fields but also a lot of fun ― for the first several years it felt like I was a student again,” Tompa recalled. “Larry Ruzzo was also learning about it, so we would attend classes and seminars together, ask a lot of stupid questions and learn a lot from each other. It’s one of the beauties of being in an academic job, you have the freedom to, say, give up your research area, become a student again and change your field of research. You couldn’t do that in most jobs and, in the end, the change paid off. Larry and I learned a lot in the area and made some good contributions.”

Allen School professor Larry Ruzzo joined the UW faculty in 1977, just one year before Tompa’s arrival. The two were collaborators in theoretical computer science and the first Allen School faculty members to work in computational molecular biology. Tompa said working with Ruzzo was one of the best aspects of his academic career, as they basically built their careers together.

“Martin and I basically ‘grew up’ together academically, and worked closely together on a variety of projects, including curriculum development, co-taught courses, service on each other’s student’s supervisory committees and many joint papers, Ruzzo said. “Martin is an academic gem — a delightful colleague, a brilliant researcher, caring and inspiring advisor, and a gifted classroom teacher.”

Members of the Allen School’s Computational and Synthetic Biology group collaborate with biologists on a wide range of computational problems that will ultimately enable them to better understand complex biological systems. Tompa’s research in this area has been extensive, particularly in motifs in genomic sequences, where his work helped biologists understand the mechanisms that regulate how, when, where, and at what rate genes express their products. An important aspect of this challenge is the identification of binding sites in the genome for the proteins involved in such regulation. Finding those binding sites is where sequence motifs come in.

In 2001, Tompa, who was also an adjunct professor in the Department of Genome Sciences by then, and graduate student Jeremy Buhler, now a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, wrote “Finding motifs using random projections.” The paper introduced a novel randomized algorithm called PROJECTION for the discovery of short sequence motifs such as protein binding sites. The duo’s approach remedied weaknesses observed in existing motif discovery algorithms and solved difficult motif challenge problems. Its impact was so great that it earned a Test of Time Award from Research in Computational Molecular Biology in 2013.

While Tompa published many papers in both theoretical computation and computational molecular biology, he took the greatest pleasure from his collaborations with interdisciplinary researchers.

“I was very proud of any paper that was really about biology,” he said. “Co-authoring with experimental molecular biologists allowed me to be a part of their discovery process. But I was also really proud of the papers I wrote with CSE graduate students, discovering new algorithms and solving problems in biology.”

Saurabh Sinha (Ph.D. ‘02), now a professor of computer science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, co-authored several papers on motifs in genomic sequences as a graduate student with Tompa and has fond memories of working in his research group. Everything, from socials at Tompa’s house to the patience and time Tompa took to help Sinha edit his papers to maximize their chance of acceptance, meant a lot to him.

“The more diffuse memory I have is of how much respect he showed his students, and how much trust he had in us, and how much independence he gave us in doing our work while also keeping an eye on the progress and providing key technical advice at the right junctures,” Sinha said. “Also, it was from him that I learned the lessons of academic and research integrity, and the importance of prioritizing means over ends.”

Amol Prakash (Ph.D. ‘06) published several papers on comparative genomics with Tompa before going on to become the founder and CEO of Optys.

“Martin was the best mentor I could have imagined. It was an honor to be his student. There are so many things that I learned from him that reflect on my thinking and writing style,” Prakash said. “I chose a non-academic career, but I am sure if I had students to advise, I would have tried to emulate a lot of what I learned from his mentoring me. I wish him the best of times in the next phase.”

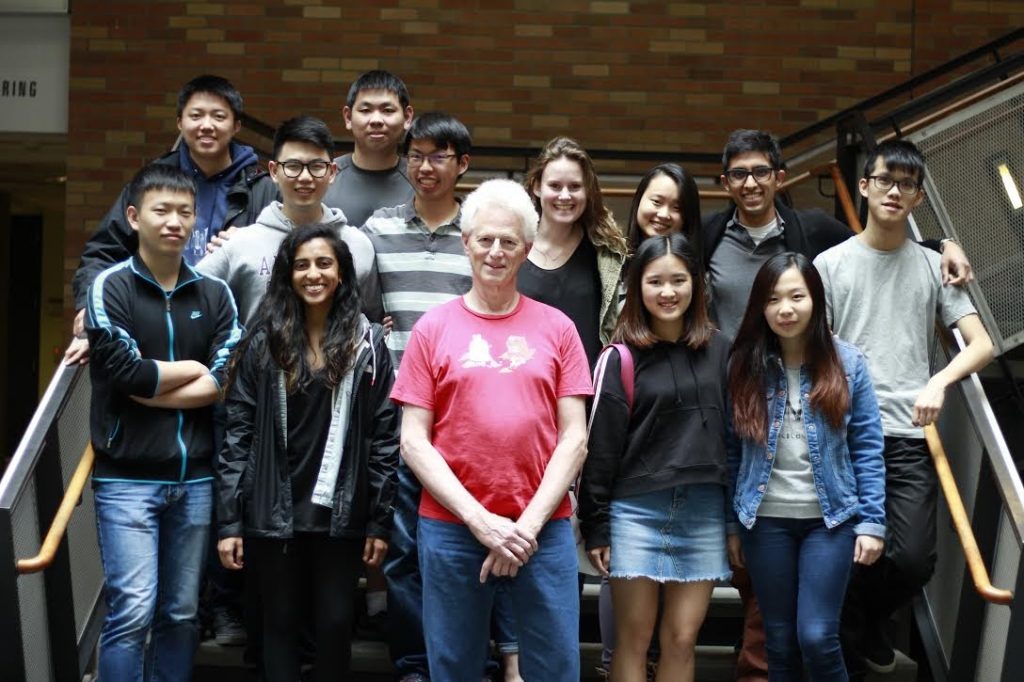

Tompa admits that, while researching and studying new disciplines was a favorite part of his career, it was the teaching that gave him the most joy. Six years ago he gave up half of his appointment as an experiment in retirement. In a move that is almost unheard of, he opted to give up research rather than teaching. Since then, Tompa has spent all of his university time teaching undergrads and loved every minute of it. It’s evident that his joy has made a positive impact on his students, and they made sure it was celebrated. In 1998 and 1999, Tompa earned back to back UW ACM Teaching Awards, the recipient of which is chosen each year by undergraduate students in the Allen School.

“In the days when lots of faculty teach using prepared PowerPoint slides, Martin has a unique way of engaging his classes and making sure that the material feels fresh,” Allen School professor Paul Beame said. “Instead of slides, Martin writes everything out on the board or using a data projector, developing each point in the lecture in interaction with the class as he goes along. Powerpoint slides can feel stale and rehearsed, Martin’s unique method makes the class feel dynamic. I marvel at how he can do it.”

Several of Tompa’s students were happy to share their best memories of their time learning from Tompa, and most of them talked about his patience, mentorship and his favorite game, Schnapsen.

Tompa learned Schnapsen from his father, who grew up in Vienna and taught him the popular Austrian card game when he was a child. Schnapsen is a two-person game that has some similarities with another well-known game, Bridge. While he enjoyed the game as a child, Tompa admits he hadn’t played it for quite some time until 2011, when two former graduate students, Dick Garner (Ph.D. ‘82) and Jeff Scofield (Ph.D. ‘85), came to him looking for a good card game they might implement on an iPhone in OCaml. Martin told them he had just the game. As it turned out, Schnapsen was the ideal game for the smaller screens of early iPhones. When Garner and Scofield sent him an early version of their app to test out, it beat Tompa far more often than not.

“I couldn’t fathom what it was doing, and I wanted to understand how it was beating me. So I started taking notes on each game,” Tompa recalled. “They had done a marvelous job, developing a program that allowed the computer in the phone to explore a lot of possible moves and look ahead quite far in the game.”

Schnapsen is the perfect pastime for computer scientists, and Tompa began a blog about the winning strategies he learned from their app, employing concepts such as expected value and other aspects of probability theory. He turned the blog into a book, “Winning Schnapsen,” the definitive guide to mastering the centuries-old game that enjoys a popular following in Europe.

Tompa also incorporated Schnapsen into his CSE 312 course on the foundations of computing, using it as a running example to illustrate various concepts from probability theory. This inspired a group of students who took the course to establish a UW Schnapsen Club. Varun Mahadevan (B.S. ‘17), a teaching assistant for four quarters of the course, fondly remembers the experience and the opportunity to learn and play Schnapsen.

“It was an absolute pleasure working with him,” Mahadevan said. “He had the most unique flavor for the class where he uses Schnapsen as a teaching tool for combinatorics. It was from this that we formed a Schnapsen club and we’d meet every Friday in a conference room on the 5th floor of the Allen Center and play cards and chat.”

One of those who fondly remembers these weekly meetups is Alex Tsun (B.S., ‘18), currently a graduate student at Stanford University.

“I remember when I first ‘met’ Martin during CSE 312 lecture more than five years ago in Winter 2015. He was so excited to be teaching probability and to share his love of Schnapsen with as many people as he could,” Tsun said. “He invited us, as he always does for his classes, to Schnapsen club on Fridays, at which I eventually became a regular. I’m not sure if he remembers this, but I first met him on the first Friday and challenged him to a game of Schnapsen. I believe I actually won my first game against him, probably by luck, and he promptly wiped me out in a second game, and in future weeks. I really enjoyed his class.”

According to Beame, when students talk about Tompa, Schnapsen is prominently mentioned, in addition to his sheer joy in teaching.

“In teaching CSE 312, which introduces CSE students to the many aspects of counting and probabilistic reasoning that are so essential in machine learning, modern algorithms, and other areas of computer science, Martin has found ways to integrate Schnapsen in the course material and homework assignments,” Beame said. “While the use of familiar games like poker is common in such courses, because this is such a new game to the students, they cannot rely on the familiar and have to think outside the box, developing real new understanding along the way.”

While students and colleagues alike will miss seeing Tompa regularly in the halls of the Allen School, Tompa says he’s excited for this new chapter of his life. He’s looking forward to spending more time with his three grandchildren in Seattle and continuing his research on his family’s genealogy. He’s working on a book about his parents and their families, who lived in central Europe in the 1930s. Their families had to flee Europe when the Nazis came to power and Tompa has been writing about what happened to them.

Although he will no longer be in the classroom, he will still have a direct impact in the lives of many students.

“On the whole, I would say that CSE has always valued its educational mission, but amidst the competing demands on everyone’s time for teaching, research, and service, I can’t think of any of my colleagues who has more consistently prioritized the needs of students, at all levels,” Ruzzo said. “Martin really cares, it shows, and he pushed all of us to do the same.”

Congratulations, Martin, enjoy your well-deserved retirement!