Many approaches to measuring and supporting city-wide mobility lack the level of detail required to truly understand how pedestrians navigate the urban landscape, not to mention the quality of their journey. Transit apps can direct someone to the nearest bus stop, but they may not account for obstacles or terrain on the way to their destination. Neighborhood walkability scores that measure proximity to amenities like grocery stores and restaurants “as the crow flies” are useful if traveling by jetpack, but they are of limited benefit on the ground. Even metrics designed to assist city planners in complying with legal requirements such as the Americans with Disabilities Act are merely a floor for addressing the needs of a broad base of users — a floor that often fails to account for a wide range of mobility concerns shared by portions of the populace.

Now, thanks to the Allen School’s Taskar Center for Accessible Technology, our ability to envision urban accessibility is taking a significant turn. In a paper recently published in the journal PLOS ONE, Allen School postdoc and lead author Nicholas Bolten and Taskar Center director Anat Caspi propose a framework for modeling how people with varying needs and preferences navigate the urban environment. The framework — personalized pedestrian network analysis, or PPNA — offers up a roadmap for city planners, transit agencies, policy makers, and researchers to apply rich, user-centric data to city-scale mobility questions to reflect diverse pedestrian experiences. The team’s work also opens up new avenues of exploration at the intersection of mobility, demographics, and socioeconomic status that shape people’s daily lives.

“Too often, we think about environments and infrastructure separately from the people who use them,” explained Caspi. “It’s also the case that conventional measures of pedestrian access are derived from an auto-centric perspective. But whereas cars are largely homogeneous in their interactions with the environment, humans are not. So what we tend to get is a high-level picture of pedestrian access that doesn’t adequately capture the needs of diverse users or reflect the full range of their experiences. PPNA offers a new approach to pedestrian network modeling that reflects how humans actually interact with the environment and is a more accurate depiction of how people move from point A to point B.”

The PPNA framework employs a weighted graph-based approach to parameterize individual pedestrians’ experiences in navigating a city network for downstream analysis. The model accounts for the variability in human experience by overlaying the existing network infrastructure with constraints based on pedestrian mobility profiles, or PMPs, which represent the ability of different users to reach or traverse elements of the network.

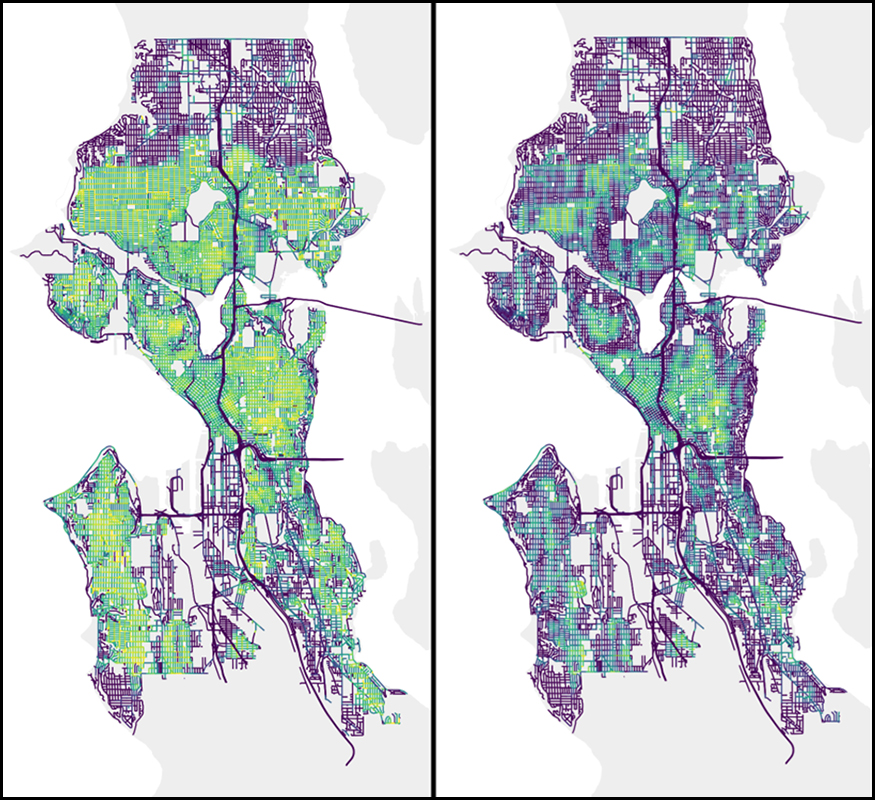

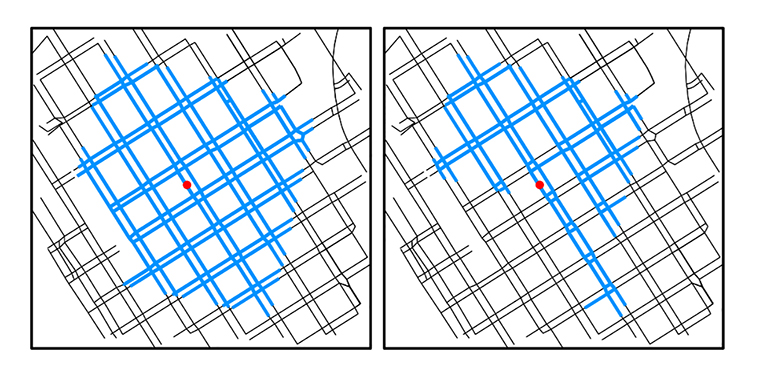

To illustrate, the team applied PPNA to a section of downtown Seattle streets using PMPs for a stereotypical normative walking profile and one representing powered wheelchair users to determine their walkshed. A walkshed is a network-based estimation of pedestrian path reachability often used by transit agencies to define a service area in relation to a particular point of interest. But whereas the typical walkshed analysis applies a one-size-fits-all approach to evaluate access, PPNA enables multiple estimates tailored to the needs and constraints of each pedestrian profile. In this case, the researchers revealed roughly one-third of the normative walking walkshed to be inaccessible to users of powered wheelchairs.

Based on their analysis, the team introduced the concept of normalized sidewalk reach, an alternative measure of sidewalk network accessibility designed to overcome biases inherent in walkshed analysis and other conventional approaches. This new, improved analysis accounts not only for the infrastructure present in the environment, but also its applicability to the humans who use it. According to Bolten, the proliferation of user data combined with new technologies have made it possible to perform such analyses at a greater level of detail than ever before.

“Crowdsourcing efforts like the OpenStreetMap initiative and emerging computer vision techniques are improving our ability to collect detailed pedestrian network data at scale. In addition, growing use of location tracking technologies and detailed surveys are enhancing our ability to model pedestrian behaviors and needs,” explained Bolten, who began working with Caspi while earning his Ph.D. from the University of Washington Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering. “By combining more detailed pedestrian network data with more robust characterizations of pedestrian preferences, we will be able to account for needs that may have been overlooked in the past while supporting the investigation of complex urban research questions.”

Among these potential questions is how connectivity for specific pedestrian profiles intersects with demographics and/or unequal access to services and amenities. For example, the authors envision that PPNA could be applied to identify where poor connectivity for one group of users overlaps with areas designated as food deserts.

While the authors focused primarily on pedestrian mobility, given that such concerns tend to be overlooked or dealt with only superficially, they note that their approach could be expanded to cover other aspects of the pedestrian experience. Additional criteria could include the perceived pleasantness of a trip, how crowded a route may be, noise levels, and more.

“When it comes to understanding how people traverse their communities, there is a vast range of user needs and preferences that are ripe for investigation to help decision-makers move beyond a one-size-fits-many approach,” observed Caspi. “By introducing quantitative measures of diverse pedestrian concerns, we can gain deeper insights into which needs are being considered and which are not across a city’s network. We hope to continue to grow our engagement with the Disability community along with city and transportation planners, to increase use of data-driven methods towards building sustainable, accessible communities.”

This latest work is a natural outgrowth of the Taskar Center’s OpenSidewalks project, which focuses on understanding and improving the pedestrian experience through better data collection. Caspi and her team also recently launched the Transportation Data Equity Initiative in collaboration with the Washington State Transportation Center (TRAC) and other public and private partners to improve data standards and extend the benefits of new mobility planning tools to underserved groups.

Read the PLOS ONE paper here, and learn more about the Transportation Data Equity Initiative here. Stakeholders who are interested in learning more or contributing to this ongoing work can contact the team here.