There are many options for mapping and route planning on a smartphone, but one thing they all have in common is their car-centric nature. Those apps that do support pedestrian navigation tend to make assumptions about a user that are at best inaccurate, and at worst dangerous.

For residents and visitors in three western Washington cities, that changes today with the release of the AccessMap mobile app. The app, which was developed by the Taskar Center for Accessible Technology housed at the Paul G. Allen Center of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington and is based off of the web-based tool of the same name, enables users of Android and iOS in the cities of Seattle, Bellingham and Mount Vernon to generate customized walking directions on the go based on their own mobility needs and preferences. The app’s release coincides with the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, an annual observance initiated by the United Nations to promote the rights and well-being of persons with disabilities in all spheres of society, including political, social, economic and cultural life.

“Many apps offer some semblance of pedestrian directions, but those directions assume a user profile that ignores the lived experience of a vast number of people,” explained Anat Caspi, director of the Taskar Center. “They make assumptions about the steepness of hills you can take, how speedy you will be, and what constitutes a safe walking or rolling environment. Some apps don’t even provide basic information like whether or not there is a sidewalk. Rather than this one-size-fits-all approach, AccessMap empowers people by giving them the ability to tailor a route that suits them as individuals.

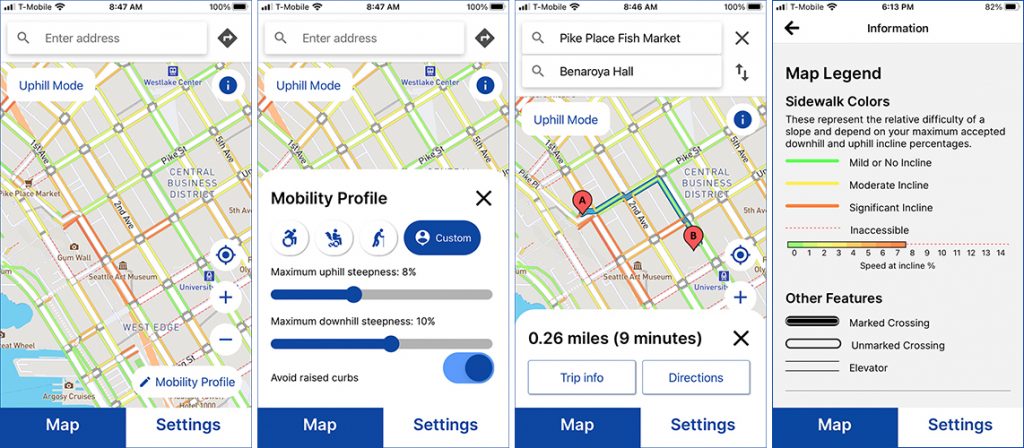

“This is significant not only because of the departure from the mass-produced apps,” she continued. “Even apps that are ‘accessibility-minded’ tend to lump together specific device use, like putting all manual wheelchair users or power wheelchair users in one category. Our research shows dramatic variability even within the same device user group, and this is also addressed by AccessMap.”

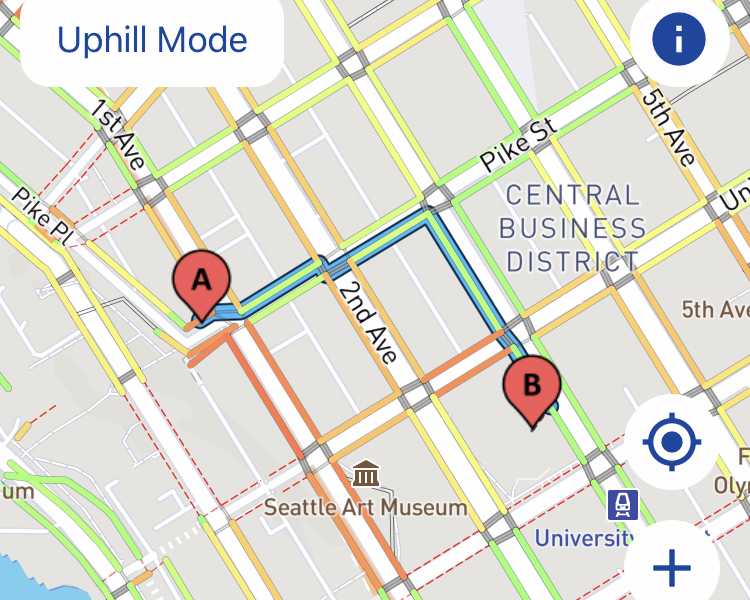

The ability to personalize their navigation options tied to real-world constraints, informed by a series of user studies during the development phase, will open up new avenues of accessibility for people with and without mobility impairments. For example, a user can request a route that takes them through intersections with “curb cuts,” which make it easier for people with strollers as well as wheelchairs to cross the street. Users can also specify a path that will enable them to avoid steep hills. The app — which is screen-reader accessible for people who are blind or low-vision — comes pre-loaded with three pedestrian profiles tailored to users who rely on a manual wheelchair, power wheelchair, or cane, along with the option to customize settings like maximum incline according to personal preference. Like other popular navigation apps, AccessMap includes color-coded maps that enable users to see at a glance which streets would be most favorable for travel; unlike those other apps, the emphasis here is on sidewalk traversability rather than automobile traffic.

Another aspect of AccessMap that sets it apart from other navigation tools: the sensitive nature of users sharing details of their personal mobility needs. For this reason, each user’s profile and preferences — for example, requests for wheelchair-accessible routes or maximum incline settings — is stored locally on their phone.

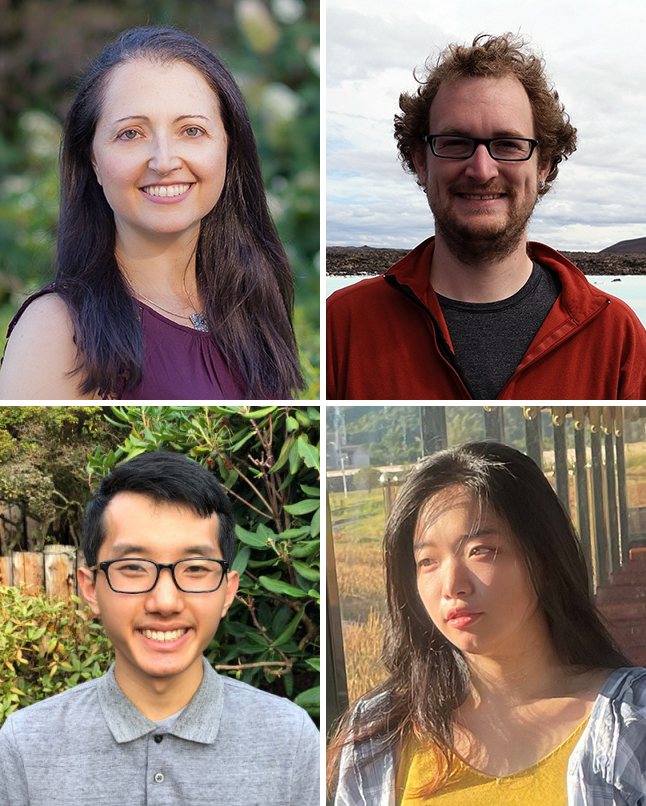

The process of turning the original web-based tool into a mobile app began in earnest in the summer of 2020 and further ramped up this past summer, when Caspi and Allen School postdoctoral researcher Nick Bolten assembled a team of undergraduate students to take on the task of translating the existing AccessMap into a user-friendly — and accessible — mobile interface. In addition to being a technical achievement, the project represented a unique learning opportunity for student researchers Xianxian Cheng, Jay Lin, and Eric Yeh.

For Yeh, AccessMap was an opportunity to combine his desire to have a positive impact on the community with the prospect of doing something he had never done before: build a mobile app from scratch.

“The main roadblock for me was having no development experience other than coursework at the time. Although I ran into a lot of bugs and issues along the way, those struggles helped me to understand how mobile apps are built and compiled,” recalled Yeh, a senior computer science major in the Allen School who is also pursuing a minor in neural engineering. “I had the opportunity to implement a large range of features such as the map, accessibility settings, and user feedback. I did not expect my very first project to expand to the scale that it is now, and it’s amazing to see how it has evolved from a barebones map to a fully functional application.”

Lin became interested in mobile app accessibility after taking the Allen School’s Interaction Programming course and making the connection between accessibility issues associated with commonly used apps and other disciplines.

“After taking classes in the Disability Studies department, I realized that there’s quite a lot of overlap between issues in technology and with legal/social justice,” explained Lin, a fourth-year student who splits their time between UW Bothell’s computer science program and the aforementioned disability studies at UW Seattle. “What’s common in these two topics is that disability rights and accessibility are often treated as an afterthought, yet this impacts a large part of your audience or user base.”

Support from the U.S. Department of Transportation paved the way for AccessMap’s move to mobile through a multi-year grant awarded to the Taskar Center and its partners in the Transportation Data Equity Initiative. Today’s release represents a step toward one of USDOT’s primary goals for that grant: to promote multimodal accessibility that includes transportation options such as bus and rail.

“Multimodal accessibility is key to providing a more useful pedestrian trip planner, as strictly pedestrian travel is usually just a subset of an overall trip,” noted Bolten, who co-led development of the original AccessMap while earning his Ph.D. from the UW Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering. “Other trip segments may involve boarding a bus, boarding a train, or driving a car, all of which must then interface with the pedestrian network. For example, choosing the right bus stop will surely depend on the accessibility of the surrounding pedestrian network, so picking the best bus and pedestrian routes aren’t independent things: they should be co-planned.

“In addition, every pedestrian trip planning question can also be thought of as an analysis of the network itself: how accessible is a city, a neighborhood, or all paths to a grocery store?” he continued. “A multimodal network will also ‘upgrade’ those questions and enable data-based conversations about public transportation and infrastructure.”

The three cities currently covered by the app are just the beginning. Caspi and her team have plans to extend coverage to the eastern side of Lake Washington, along the Bellevue-Redmond corridor, as well as to the city of Austin, Texas. The group is also collaborating with municipalities, transit agencies and advocacy groups to collect data for new cities, including Los Angeles, California and four Latin American cities as part of a partnership with international nonprofit G3ict and Microsoft’s AI4Accessibility initiative, to extend the app’s coverage even further — plans that align with the Taskar Center’s mission of designing for the fullness of the human experience, which will enable people to fully participate in civic life.

That goal is one that AccessMap’s student developers will carry with them into their future work.

“Working on AccessMap has helped me to see how people see, hear, feel, touch, and perceive the world in their own ways. There are some experiences we may take for granted, but we should always remember there may be constraints that are invisible to our eyes which might harm others who have different ways of interacting with the world on a daily basis,” said Cheng, a senior studying informatics and user experience designer for the AccessMap app. “I feel honored that I could be a part of this digital translation that leverages accessible user experience.”

The AccessMap mobile app is available now from Apple’s App Store (iOS) and Google Play (Android). Government agencies, municipalities, institutions and community organizations interested in having their city included in the next release of AccessMap may submit their request to the team via email at opensidewalks@gmail.com.