“You are what you eat,” as the saying goes. But not everyone has the same degree of choice in the matter. An estimated 19 million people in the United States live in so-called food deserts, where they have lower access to healthy and nutritious food. More than 32 million people live below the poverty line — limiting their options to the cheapest food regardless of proximity to potentially healthier options. Meanwhile, numerous studies have pointed to the role of diet in early mortality and the development of chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer.

Researchers are just beginning to understand how the complex interplay of individual and community characteristics influence diet and health. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Washington and Stanford University recently completed the largest nationwide study to date conducted in the U.S. on the relationship between food environment, demographics, and dietary health with the help of a popular smartphone-based food journaling app. The results of that five-year effort, published today in the journal Nature Communications, should give scientists, health care practitioners and policymakers plenty of food for thought.

“Our findings indicate that higher access to grocery stores, lower access to fast food, higher income and college education are independently associated with higher consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, lower consumption of fast food and soda, and less likelihood of being classified as overweight or obese,” explained lead author Tim Althoff, professor and director of the Behavioral Data Science Group at the Allen School. “While these results probably come as no surprise, until now our ability to gauge the relationship between environment, socioeconomic factors and diet has been challenged by small sample sizes, single locations, and non-uniform design across studies. Different from traditional epidemiological studies, our quasi-experimental methodology enabled us to explore the impact on a nationwide scale and identify which factors matter the most.”

Althoff ‘s involvement in the study dates from when he was a Ph.D. student at Stanford working with professor and senior author Jure Leskovec and fellow student and co-author Hamed Nilforoshan. Together with co-author Dr. Jenna Hua, a former postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University School of Medicine and founder and CEO of Million Marker Wellness, Inc., the team analyzed data from more than 1.1 million users of the MyFitnessPal app — spanning roughly 2.3 billion food entries and encompassing more than 9,800 U.S. zip codes — to gain insights into how factors such as access to grocery stores and fast food, family income level, and educational attainment contribute to people’s food consumption and overall dietary health.

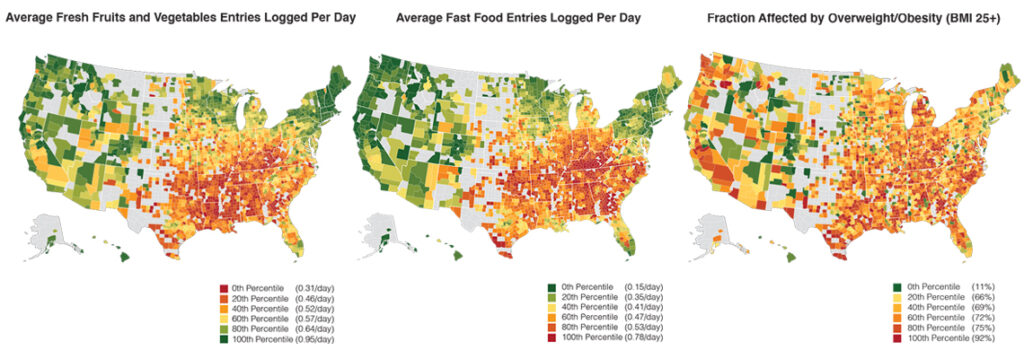

The team measured the association of the aforementioned input variables with each of four dietary outcomes: fresh fruit and vegetable consumption, fast food consumption, soda consumption, and incidence of overweight or obese classified by body mass index (BMI). To understand how each variable corresponded positively or negatively with those outcomes, the researchers employed a matching-based approach wherein they divided the available zip codes into treatment and control groups, split along the median for each input. This enabled them to compare app user logs in zip codes that were statistically above the median — for example, those with more than 20.3% of the population living within half a mile of the nearest grocery store — with those below the median.

Among the four inputs the team examined, higher educational attainment than the median, defined as 29.8% or more of the population with a college degree, was the greatest positive predictor of a healthier diet and BMI. All four inputs were found to positively contribute to dietary outcomes, with one exception: high family income, defined as income at or above $70,241, was associated with a marginally higher percentage of people with a BMI qualifying as overweight or obese. But upon further investigation, these results only scratched the surface of what is a complex issue that varies from community to community.

“When we dug into the data further, we discovered that the population-level results masked significant differences in how the food environment and socioeconomic factors corresponded with dietary health across subpopulations,” noted Nilforoshan.

As an example, Nilforoshan pointed to the notably higher association between above-median grocery store access and increased fruit and vegetable consumption in zip codes with a majority of Black residents, at a 10.2% difference, and with a majority of Hispanic residents, at a 7.4% difference, compared to those with a majority of non-Hispanic white residents, where he and his colleagues found only a 1.7% difference. These and other findings indicate that factors such as proximity to grocery stores or higher income, on their own, are not sufficient for people to bypass the drive-thru or kick the (soda) can to the curb — and that future attempts to address dietary disparities need to take variations across zip codes into account.

“People assume that if we eliminate food deserts, that will automatically lead to healthier eating, and that a higher income and a higher degree lead to a higher quality diet. These assumptions are, indeed, borne out by the data at the whole population level,” explained Hua. “But if you segment the data out, you see the impacts can vary significantly depending on the community. Diet is a complex issue! While policies aimed at improving food access, economic opportunity and education can and do support healthy eating, our findings strongly suggest that we need to tailor interventions to communities rather than pursuing a one-size-fits-all approach.”

Althoff believes that both the team’s approach and its findings can guide future research on this complex topic that has implications for both individuals and entire communities.

“We hope that this study will impact public health and epidemiological research methods as well as policy research,” said Althoff. “Regarding the former, we demonstrated that the increasing volume and variety of consumer-reported health data being made available due to mobile devices and applications can be leveraged for public health research at unprecedented scale and granularity. For the latter, we see many opportunities for future research to investigate the mechanisms driving the disparate diet relationships across subpopulations in the U.S.”

Read the paper in Nature Communications here. Access the publicly available data and code associated with the study here.