By the end, colors filled the room.

Blues, yellows, pinks and reds, all bobbing about, to and fro. When the clacking stopped, the popping began. And the trio of Allen School students, triumphant, smiled.

“Team communication and coordination is the key to success,” said their bespectacled coach, who was watching from afar. “It’s a bonding experience.”

The International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC) carries a colorful tradition besides an easy way for competitors to gauge where they stand in the rankings. As each team solves a problem, a balloon rises above their station, buoyancy abounding both above and below. A clutch of balloons spells success. A dearth of them adds pressure.

A few tables over, crews from Stanford and Carnegie Mellon University were tapping away with gusto. Around the ballroom on The University of Central Florida’s campus, balloons rose left and right. A chorus of keyboard clicks urged the contestants on as screens bathed their faces in a hazy blue light, and the timer continued to tick in giant white digits above the stage.

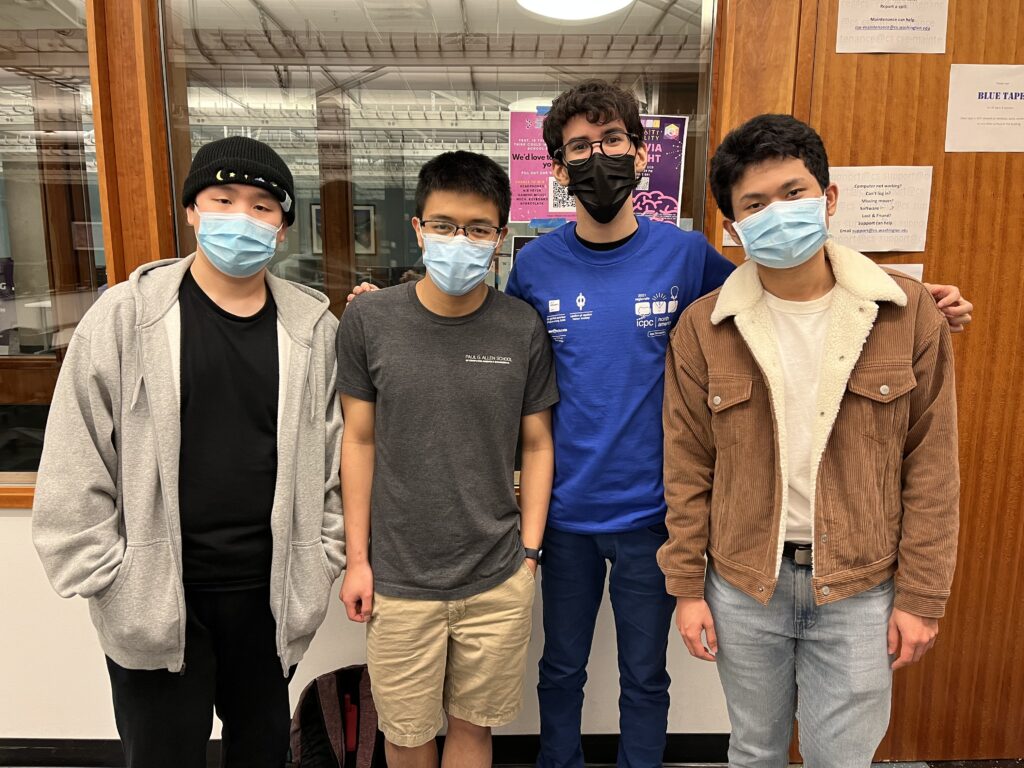

The University of Washington team, made up of then seniors Phawin Prongpaophan (B.S., ‘22), Milin Kodnongbua (B.S., ‘22) and Nathan Akkaraphab (B.S., ‘22), sat heads together, trying to decipher a riddle that had, so far, perplexed their competition. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the three dove in and submitted their response to the infamous problem “A,” their eyes fixed on the electronic scoreboard that announced the results as they arrived.

The trio waited. Two submissions were pending — theirs and MIT’s. The scoreboard flashed green, signaling correct answers from both teams.

But who solved it first?

The answer came attached to a string. The UW team, dubbed “new-final-final-2,” received the star-shaped first balloon, edging MIT by 3 seconds.

“Problem A was an interesting situation,” said Kodnongbua, now a Ph.D. student in the Allen School. “It wasn’t until we got the first-to-solve balloon that we knew we were ahead.”

The team would ride its momentum to a 10th-place finish in the ICPC North America Championship and a spot in the 46th Annual ICPC World Finals scheduled to be held in Egypt next November. Their achievement marks the first time in 22 years that a UW team has advanced to the world finals.

But the team, which is advised by Allen School professor Stuart Reges, is focused on the process, not outcomes.

“Our goal is to challenge ourselves by solving unprecedentedly hard and complex problems,” Kodnongbua said. “They are like a brain teaser that helps us stretch our thoughts and form a systematic way of solving problems.”

Victor Reis, the team’s coach, has been through the process many times before. A veteran of the competitive programming circuit, the Ph.D. student in the Theory of Computation group, competed twice as an undergraduate at Cornell and went on to coach its team as a junior and a senior.

At the UW, Reis has been at the helm since 2019. Past experiences in the competition have taken him to Marrakesh, Phuket and Beijing.

But this year marked the first time he — and the team, for that matter — have been to Orlando, Florida.

“So we had to go to Disney World,” Reis said, smiling.

The day they arrived for the national competition back in May, the members headed to the famed amusement park, braving roller coasters, water rides and encounters with Mickey Mouse. It’s the type of bonding that builds the teamwork needed during competition, Reis said, and stays with students far longer than wins or losses.

For example, nothing toughens a group up like surviving The Tower of Terror.

“Surprisingly scary,” Reis said. “I think that was our favorite.”

To field the team, Reis took top squads from the programming contest he runs every winter, which garners interest from an estimated 100 students, to the regional ICPC competition held in March. There, Prongpaophan, Kodnongbua and Akkaraphab placed first, securing their place at nationals in sunny Orlando later that spring.

In between, they set to work, practicing weekly before the national competition. They organized mock contests, solving past problems within the allotted five-hour time limit to mimic the actual event.

They’ll continue with this practice schedule until the world finals next year. Normally, they’d be on their way to the finals taking place the November following the national competition. But due to the pandemic, the schedule was shifted back another year. Qualifiers from 2022 will compete in a “mega” competition in fall 2023, Reis said, along with qualifiers from next year’s nationals.

So, given the long wait, keeping their skills sharp remains a focus for the team members.

“We want to do our best,” Kodnongbua said. “These problem-solving and coding skills deteriorate over time if not touched regularly.”

“Be it luck or change in perspective, I consider us to be fortunate enough to get to advance to the world finals,” added Akkaraphab, who comes from a mathematics background and is currently pursuing his master’s at UW in applied and computational mathematics. “My competitive programming knowledge is not on par with [my teammates], but I hope that I can bring something from the other side — math — to the table, and I will learn something new from competitive programming.”

To pass the time, they’ll hone reflexes and brush up on areas of weakness in previous competitions. At nationals, for instance, the final problem they solved produced “a messy code” and three 20-minute penalties. A key observation regarding Fibonacci sequences sent them coding down a longer and more-winding path.

“We started by asking ourselves, ‘how can we solve this problem in one-dimensional?’” said Prongpaophan, who is currently pursuing his master’s degree in computer science at Northwestern University. “After we had the answer to our question, we tried to reduce the original 2-D problem into a 1-D that we know how to solve.

“Shortly after the contest, we realized that we can simply use 2-D data structure to solve the problem, which has better time complexity and more importantly, is much easier to code than our square root decomposition,” Prongpaophan continued. “Thus, we took an unnecessarily challenging path to the final.”

But, in the end, they solved it — the tipping point that sent them to the world finals.

“The final is going to be a magnitude harder than the nationals,” Kodnongbua said. “There are some concepts, like string and graph manipulation, that are currently not our strength, and so we want to strengthen our knowledge base and make sure we are up for the contest.”

Should they succeed, the only strings left to manipulate will be attached to balloons.

“Just have fun,” Reis said, encouraging future students interested in competing. “Try to enjoy the experience, because that’s what you’re there for, right? If you learn something in the process, it’s an A plus.”