Every year, the Allen School recognizes two alumni who have made outstanding contributions to computing and to society. Each of our 2018 Alumni Impact Award recipients, Yaw Anokwa and Eileen Bjorkman, exemplify how a computer science education offers multiple avenues to achieving success and making an impact. Anokwa and Bjorkman will be formally honored as part of the Allen School’s graduation celebration this evening on the University of Washington Seattle campus.

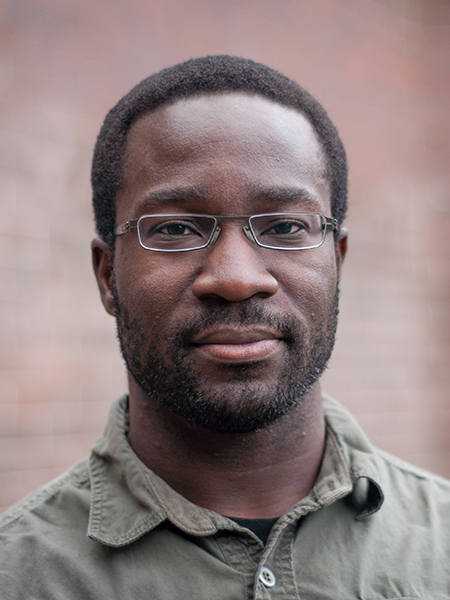

Yaw Anokwa (Ph.D., ’12) engineers solutions with a global reach

In January 2018, Somalia’s Federal Ministry of Health announced a campaign to vaccinate more than 726,000 young children in the Banadir region against poliovirus. Although no new cases of polio had been reported at the time of the announcement, several sewage samples taken in the nearby capital city of Mogadishu had recently tested positive for the virus. The Somali government, aided by the World Health Organization and UNICEF, hoped to stave off a public health emergency by vaccinating children who were either too young or had been passed over in previous campaigns due to ongoing conflict in the region.

In January 2018, Somalia’s Federal Ministry of Health announced a campaign to vaccinate more than 726,000 young children in the Banadir region against poliovirus. Although no new cases of polio had been reported at the time of the announcement, several sewage samples taken in the nearby capital city of Mogadishu had recently tested positive for the virus. The Somali government, aided by the World Health Organization and UNICEF, hoped to stave off a public health emergency by vaccinating children who were either too young or had been passed over in previous campaigns due to ongoing conflict in the region.

The rapid mobilization was justified. Prior to the introduction of effective vaccines in the mid-20th century, polio was responsible for hundreds of thousands of cases of childhood paralysis in industrialized countries each year. While the Global Polio Eradication Initiative has made great strides toward eliminating the virus worldwide, there are areas of sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East where political instability, inadequate infrastructure, and other challenges cause polio to remain a threat even today. Banadir had proved particularly vulnerable; it reported the highest number of poliovirus infections — 72 out of a total 199 cases — during the Horn of Africa outbreak just four years earlier.

To provide public health officials with timely and accurate information as the campaign progressed, more than 200 personnel were trained on a set of open-source mobile data collection tools known as the Open Data Kit, or ODK. The software that powers ODK had been started roughly a decade ago and half a world away, by a team of researchers at the University of Washington. That team included 2018 Alumni Impact honoree Yaw Anokwa.

Anokwa was born in Ghana and moved to the United States when he was 10 years old after his father, a college professor, accepted a job at Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana. Anokwa knew from a young age that he wanted to be an engineer — “I broke a lot of toys as a kid, trying to see how they worked” — but once he discovered programming in college, his interest switched from hardware to software. He went on to simultaneously earn bachelor’s degrees in computer science and electrical engineering from Butler University and Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, respectively. When it came time to choose a graduate school, Anokwa admitted he didn’t have a particularly strong feeling about UW. Not, that is, until he attended prospective student visit days.

“Everyone was friendly, kind, thoughtful,” Anokwa recalled. “The people I met at UW CSE treated me as a person who had something of value to contribute.”

When he arrived in Seattle in fall 2005, Anokwa thought he would study artificial intelligence. He abandoned that notion fairly quickly after he developed a rapport with professor Gaetano Borriello, who sparked his interest in ubiquitous computing and human computer interaction. Shortly after he began working with Borriello, Anokwa stumbled onto information and communication technologies for development, or ICTD, because of the groundbreaking research Tapan Parikh (Ph.D., ’07) was doing with his CAM system in rural India. Anokwa’s interest reached a high during a colloquium featuring alumnus Neal Lesh (Ph.D., ’97). Lesh, who was pursuing a second graduate degree in international public health at Harvard at the time, had returned to his alma mater to deliver a talk titled “Gadgets for Good: How Computer Researchers Can Help Save Lives in Poor Countries.”

“Neal was this sort of wandering guru of ICTD, and his presentation on how a little bit of tech from one person could have a direct and positive impact in the service of social justice blew me away,” said Anokwa. “The point of most academic research is to explore questions for which a solution might be 20 or 30 years away.

“Maybe that’s why I was never a great researcher,” he continued. “I saw plenty of current problems, so why worry about future problems? Let’s build stuff that’s useful today! ODK is a great example of this; from day one, people found it useful.”

Inspired by Lesh’s example, Anokwa took a break from UW after earning his Master’s degree and traveled to Rwanda to work with an organization called Partners in Health. The group was deploying an electronic alternative to paper medical records, called OpenMRS, in the small town of Rwinkwavu. In Rwanda, Anokwa observed how the reliance on paper records hindered the care of patients with chronic diseases such as AIDS and tuberculosis — and saw how OpenMRS made things better.

While OpenMRS had real potential to streamline workflow and improve outcomes, the time and the training required of doctors and nurses trying to use the system proved to be obstacles. Since the point of the system was to improve direct care, Anokwa set about simplifying the interface for accessing patient information, mapped to clinical workflow. A new search module enabled providers to easily locate patients in the system by name, location, or cohort, while a new patient summary module offered a concise overview of patient data in an easy-to-read, printable format. Additional features, such as automated alerts and the ability to generate customized graphs for specific patient data points, provided more robust functionality.

What was intended to be a three-month break had turned into six, and then Anokwa heard from Borriello. His advisor informed him that he was taking a sabbatical from UW to work on a new mobile data collection project at Google; Anokwa’s fellow graduate students, Carl Hartung and Waylon Brunette, planned to work on the project with him. The goal was to create a set of modular, customizable tools for data collection that would leverage the new Android operating system as well as the growth in mobile technologies. The tools would be built on open standards and be, in the team’s words, “easy to try, easy to use, easy to modify, and easy to scale.” After some back and forth, the three convinced Anokwa to return to Seattle and join them.

“Android was just coming out, but Gaetano already recognized its potential to drive innovation in the ICTD space,” Anokwa explained. “From my experience with OpenMRS, and some convincing from Gaetano, Carl, and Waylon, I could see that it was a good problem to solve.”

ODK started out as a set of two complementary tools: ODK Collect, a tool for survey-based data gathering that can be used even without network connectivity; and ODK Aggregate, a cloud-like service for storing, managing, and publishing data. While OpenMRS had offered a desktop solution to the “paper problem” in healthcare, ODK enabled people to create and act on digital records for a variety of purposes in the field — sometimes literally. In one of the first deployments of the new platform, Google and the Grameen Foundation used ODK to gather data on the availability of phone-based services in rural Uganda to develop an app offering agricultural advice to farmers.

In another early example, Anokwa and Hartung traveled to Kenya to work with one of the largest HIV treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa, AMPATH. By furnishing its community outreach workers with phones running ODK, the group was able to improve in-home testing and counseling for over a million people in rural parts of the country. Anokwa subsequently worked with AMPATH to field-test a mobile phone-based clinical decision system called ODK Clinic, which formed the basis of his Ph.D. dissertation under the guidance of Borriello and Parikh, then a faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley. ODK Clinic drew upon Anokwa’s experience working on OpenMRS and ODK, providing physicians with point-of-care access to patient summaries and reminders to improve the quality of care for patients living with HIV.

The more people used ODK, the more uses people seemed to find for it. Since its inception, ODK has helped members of the Surui tribe and the Brazilian Forest Service to monitor conditions in the Amazon rainforest, the Jane Goodall Institute to track conservation efforts in Tanzania, The Carter Center to observe elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo — even an astronaut on the International Space Station to track the progress of the Carbon for Water program. As the user community grew, so did the tools, including a drag-and-drop form designer known as ODK Build developed by undergraduate researcher Clint Tseng (B.S., ’10) and a form management tool called ODK Briefcase. To date, the ODK website has seen traffic from nearly every country, and Anokwa estimates that millions of users have used ODK or its derivatives worldwide.

Some of this growth has been spurred by Nafundi, a consulting company Anokwa co-founded with Hartung in 2011 when the pair realized how many large organizations wanted to use ODK but needed help. Nafundi provides that help in the form of software development and technical support. After Hartung departed in 2016 to focus full-time on a new startup company, Anokwa’s partner in life, software engineer, and former Allen School lecturer Hélène Martin (B.S., ’08) stepped in and became his partner in business, too. Together, the couple manage Nafundi’s small and distributed team of developers from their home base in San Diego, California.

Anokwa and Martin share the technical work and community leadership, and over the last year they have been focused on adding much needed functionality to the most widely deployed ODK tools and implementing community-oriented processes project-wide. As Anokwa explains, “We use a combination of grants and client work to feed the open-source project. Our hope is that the investments we are making now will enable other organizations to step forward and help make the ODK pie bigger.”

Following Borriello’s passing in 2015, Allen School professor Richard Anderson had assumed management of ODK. Now, he and his team are working with Anokwa and others in the ODK community to morph it into a stand-alone entity, with the hope that independence will lead to even greater impact. Anokwa is particularly motivated to ensure the transition is successful because, in his view, ODK represents Borriello’s legacy to the world.

“ODK has become the de facto data collection tool for global development, and the project’s continued success is a responsibility that I take very seriously,” noted Anokwa. “It’s what the folks who depend on ODK deserve, and it’s what Gaetano wanted.”

“Yaw’s work in creating and supporting Open Data Kit shows the power of computer science to change the world,” said Hank Levy, Allen School Director and Wissner-Slivka Chair. “ODK is helping to improve the lives of people in underserved communities around the globe, and Yaw’s commitment is an example for all of us.”

When asked why he thought ODK took off in the way that it has, Anokwa cited a variety of factors. “Luck and timing both played a part,” Anokwa admitted, “but also, it was free — free as in no cost, and free as in no restrictions. Anyone can take ODK and adapt it to their needs.

“I would like to believe that the care and attention we provided to our user community was also a factor, because I’ve spent a lot of time responding to emails and giving talks about ODK,” he laughed. But ultimately, he points out, software has to work.

Perhaps there is no better example of why the software “has to work” than the fight to eradicate polio. “The vaccinators in Somalia are putting their lives on the line, going house to house in one of the most dangerous places in the world,” noted Anokwa. “They may only get one chance to vaccinate a child, so the software has to be deployable by regular people and work the first time, every time.”

It’s the users, then, who are the real heroes of this tale, in Anokwa’s view — them, and the people with whom he has collaborated over the past 10 years.

“I get an unfair share of the credit for all of this,” Anokwa said. “ODK’s success is made possible by a community of contributors who believe that together, the little data collection project I helped to start can help make the world a better place.”

According to one of his former Ph.D. advisors, Tapan Parikh, Anokwa’s emphasis on community has been at the heart of ODK and its impact — even if he did take some convincing at first.

“I remember that Yaw was initially apprehensive about taking on the ODK project for his dissertation. He was concerned that there was not enough research content in an area that had already been well-explored by others, including myself,” Parikh said. “I tried my best to tell him that there was a lot more left to do, and that the potential for impact was huge.

“I’m so glad that Gaetano was eventually able to convince Yaw to take this project on,” he continued. “It is no overestimation to say that ODK is one of the most influential ICTD systems projects to come out of the academic realm, and that a large part of the credit for building and sustaining the open-source community around ODK should go to Yaw.”

Looking back on what he has gained from his Allen School education, Anokwa observed, “UW in general, and Gaetano in particular, gave me the space to try things, even if they seemed unreasonable. I gained the confidence to head in the direction of the unknown, and to persevere. Along the way, I learned that I’m never going to be the smartest person in the room — as anyone who remembers me from algorithms class can attest! — but with a little luck, everyone can make their mark. I don’t know if I deserve this award, but my hope is that the attention it brings can inspire someone to start their journey in the same way that Gaetano, Tapan, and Neal inspired me to start mine so many years ago.”

Eileen Bjorkman (B.S., ’79) earns her wings

Alumni Impact Award recipient Eileen Bjorkman didn’t set out to study computer science. When she first arrived at the University of Washington in 1975, she was looking forward to earning her degree in aeronautical engineering.

Alumni Impact Award recipient Eileen Bjorkman didn’t set out to study computer science. When she first arrived at the University of Washington in 1975, she was looking forward to earning her degree in aeronautical engineering.

It was a reasonable plan; after all, jet fuel practically runs through Bjorkman’s veins. Her father, Arnold Ebneter, was an aviation enthusiast from an early age who spent more than 20 years in the Air Force as a pilot and engineer. Her mother, Colleen, was an amateur pilot, having been bitten by the flying bug while earning her Girl Scout aviation merit badge. Growing up in various locations in the south and midwest, Bjorkman was surrounded by airplane books, airplane magazines — even miscellaneous airplane parts — vying for space alongside the usual detritus of family life. There was also the family plane, a Beechcraft Bonanza affectionately known as “Charlie,” with seating for six. Bjorkman and her three sisters all flew before they could walk.

“One of the problems with growing up in an aviation family is that you don’t remember your first flight,” observed Bjorkman. “My father took me up in the family plane when I was three weeks old. Until I was eight or nine, I just assumed every family was like ours and flew airplanes on weekends.”

After Ebneter retired from the Air Force in 1974, he accepted a job as an engineer at the Boeing plant in Renton, Washington. Shortly after the family completed the move to the Pacific Northwest, Bjorkman enrolled in UW. Her sophomore schedule included statics — an introductory engineering course — and the FORTRAN programming language. For reasons she can no longer remember, she disliked statics so much that she decided she wasn’t cut out for aeronautical engineering after all. Having discovered that she liked programming, she opted to pursue computer science instead.

One day on the bus, Bjorkman struck up a conversation with the late Ira Kalet, a faculty member in UW’s Department of Radiation Oncology and, later, adjunct professor of Computer Science. Kalet suggested that Bjorkman apply for a job as a student programmer at the Northwest Medical Physics Center, which at the time was part of UW’s Regional Medical Program. She took his advice and soon found herself developing program interfaces to aid doctors in devising radiation treatment plans for cancer patients. Bjorkman liked the fact that her code was being used to save lives. The pay wasn’t bad, either.

“I earned four dollars an hour, which seemed like a lot in those days,” Bjorkman recalled with a laugh. “And the equipment was cool, too. Not only did my machine have a whopping 64K of memory, but it had 64K of graphics memory. That was a big deal.”

After graduating from UW in 1979, Bjorkman accepted a full-time position at the center, where she obsessed over ways to reduce the runtime of such complex programs.

“Some of those programs could take as long as 45 minutes,” she noted. “I was always looking for ways to cut that down. When I was able to reduce it to 30 minutes, wow — that was an exciting day!”

Bjorkman still felt her work was worthwhile, but she couldn’t picture herself programming for the rest of her life. Looking to expand her professional horizons, Bjorkman headed to the UW placement center. And it was from there that her career took off in a new — and yet, familiar — direction.

“I went to the placement center to meet with a recruiter from Boeing,” Bjorkman explained. “While I was waiting, I started chatting with an Air Force recruiter who happened to be there. The next thing I know, I’m filling out stacks of paperwork, and the Air Force is offering me a place in its accelerated engineering program.”

Bjorkman enrolled in the Air Force Institute of Technology thinking she would earn a second bachelor’s in electrical engineering, but her superiors had other ideas. She was directed to the aeronautical engineering program — the subject she had intended to study back at UW, before succumbing to FORTRAN’s charms. Bjorkman couldn’t believe it at first, but then everything clicked into place.

“The two degrees meshed together better than I ever thought they would,” recalled Bjorkman. “And right around that time, airplanes started to become computerized.”

At that point, Bjorkman faced another career-defining decision. By the mid-80’s, the Air Force had reversed an earlier policy prohibiting women from flying, but she couldn’t meet the stringent vision requirements to be a pilot. However, she could be a flight test engineer, which would still put her in the cockpit — just in the back seat gathering data, rather than in front at the controls. So in 1985, Bjorkman became only the sixth woman ever to enroll in the Air Force’s Test Pilot School. By that point, she was used to being one of only a few women, if not the only woman, making her way in a male-dominated field.

“At UW, I got used to being the only woman in a lot of my engineering classes, and there were maybe three other women besides me studying computer science,” said Bjorkman. “When I first graduated from Test Pilot School, I was the only female Test Pilot School graduate on base.”

Bjorkman would go on to notch over 700 hours of flight time in more than 25 different aircraft as a flight test engineer, instructor, and test squadron commander. On the ground, she assumed a series of management and leadership roles focused on improving the safety and effectiveness of various Air Force systems. It was these mid-career positions, beginning in the early 1990s, that demonstrated just how useful her combination of degrees could be.

For her first assignment at the Pentagon, Bjorkman was put in charge of air-to-air combat modeling to evaluate how adjustments to a fighter jet’s aerodynamics and systems would affect the outcome under various conditions. Bjorkman found herself once again using FORTRAN — this time, writing data scripts for a program simulating in-air dogfights — and managing a small network of computers. Her recommendations were used by the Air Force to help decide what to buy and modify for its fighter aircraft.

“I recognize the fingerprints of what I worked on 20, 25 years ago still being put into practice today,” said Bjorkman. “It is gratifying to see that the simulations I ran back then are still contributing to a better Air Force.”

Her next two assignments took her to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, home of the Holloman High-Speed Test Track. The 10-mile, precision-aligned track enables the Air Force to field-test new systems before making them operational. As commander of the 846th test squadron, which operates the test track, she led the testing of high-speed missile delivery systems and new ejection seat designs — the latter intended to accommodate lower weight people, such as the women who were becoming more prevalent among the pilot ranks. The following year, she assumed command of the 746th, which was responsible for testing global positioning system (GPS) satellites and equipment. At the time, GPS was on the cusp of making the leap from military to consumer applications. Looking back, Bjorkman finds this period of her career particularly satisfying in the knowledge that the systems she worked on wound up benefiting not just the Air Force, but the whole world.

Bjorkman retired from active duty as a colonel in 2010, at which point she began serving in a civilian capacity. Along the way, she earned two master’s degrees from the armed forces — one in aeronautical engineering and the other in national resource strategy — followed by a Ph.D. in systems engineering from The George Washington University. She currently serves as the Air Force’s Deputy Director of Programs, Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Plans, Programs and Requirements. In that role, she oversees the $605 billion Future Years Defense Plan, the five-year budget plan for investing in technology, equipment, and personnel to maintain the Air Force’s readiness and evolve its capabilities in line with new advances and emerging threats.

In her spare time, Bjorkman has clocked more than 2,000 hours of civilian flight time. Despite aviation’s defining presence throughout her childhood, Bjorkman didn’t learn to fly while she was growing up. This was partly because Charlie was too advanced for a novice pilot, but also, she admitted, “I wasn’t that interested in flying until I joined the Air Force. Then I figured I better learn.”

One activity that Bjorkman has consistently remained passionate about since childhood is writing. Her first published work came at the tender age of nine when, she said with lingering disbelief, “I wrote a stupid story and sent it into a kids’ magazine — and they published it!” Her first paid writing assignment — outside of technical reports and military briefings — was a short piece that appeared in Air & Space Magazine titled “Maybe I Will Pass on That Coffee.” The article relays a harrowing, yet humorous, firsthand account of being stuck in the back of an F-16 with a full tank of fuel and a full bladder, thousands of feet above the nearest bathroom. Since then, she has written numerous articles for Air & Space, Aviation History, the Daily Herald of Everett, and others.

Last March, Bjorkman published her first book, The Propeller under the Bed: A Personal History of Homebuilt Aircraft, after taking a non-fiction writing course through UW Continuing Education. The idea for the title originated with Bjorkman’s mother, inspired by the wooden propeller that her husband had stashed under their bed when he dreamed of building his own plane. The book was a labor of love for Bjorkman, and while it took fewer than five years to complete, it was a lifetime in the making.

Propeller follows her father’s journey as an aviation enthusiast and engineer who, at the age of 82, set a new world record for the longest nonstop flight, measured as a straight-line distance, in a lightweight C-1aI class aircraft. On July 25, 2010, Ebneter took off from Paine Field in Everett, Washington in his “E-1,” an all-metal airplane that he designed and built himself. Around 2,328 miles and a little over 18 hours later, he touched down at Shannon Airport in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Ebneter had beaten the old record by nearly 114 miles — overcoming a faulty fuel gauge and an uncooperative headwind along the way. As the story unfolds, Bjorkman weaves in a history of homebuilt aircraft and the people who dared to reach for the sky on their own terms. As it turned out, recounting the story of her father’s dream was the perfect opportunity to fulfill one of her own.

“Writing a book has been a lifelong dream for me, but I never expected that it would turn into a project about my family and the dreams of thousands of other amateur aircraft homebuilders throughout the world,” Bjorkman wrote on her blog at the time. “During my research, I gained a much better understanding of not only the history of aviation in the United States but also learned much about my own parents and other relatives. I feel very fortunate to have had this opportunity to document all of this for future generations to enjoy.”

And what of that computer science degree Bjorkman earned nearly four decades ago — how did her time at UW influence and inspire the high-flyer she would later become?

“I’ve always thought of myself as an engineer, rather than a computer scientist, but there’s no doubt that my CS degree gave me the building blocks for success. Time and again, I found I could do things with computers that my colleagues could not — or at least, took my colleagues longer to learn,” Bjorkman explained. “Even today, that fundamental knowledge is still valid. But more important than the mechanics of learning to code, my degree gave me confidence to rise to the occasion when challenged and to accomplish things that I didn’t think I was capable of doing.”

“We always emphasize to students that a degree in computer science will prepare them for the broadest imaginable range of careers — Eileen exemplifies this,” said Allen School professor Ed Lazowska, Bill & Melinda Gates Chair in Computer Science & Engineering. “She proved that with a CS degree, the sky’s the limit — literally and figuratively! She was also a trailblazer for women in the service of her country. We’re incredibly proud of all that Eileen has accomplished, and we’re delighted to be able to recognize her with our 2018 Alumni Impact Award.”

Asked what advice she would offer students today, Bjorkman harkened back to the words of her examiner when she earned her private pilot’s license. “He impressed upon me that earning my license was not the end of my education as a pilot, but the beginning — that it is actually a license to learn,” she recounted. “Whatever you get your degree in, view that as your license to learn.

“And to students of computer science: don’t think of yourself as just a ‘computer scientist,'” she urged. “Think of yourself as a person with a computer science degree, which opens up all kinds of possibilities for you to go out and do great things.”

Learn more about Allen School alumni who are doing great things on our Alumni Impact Award webpage here.