To say Anat Caspi’s mission is pedestrian in nature would be accurate to some degree. And yet, when looked at more closely, one realizes it’s anything but.

In 2015, the Allen School scientist was thinking about how to build a trip planner that everyone could use, similar to Google Maps but different in striking ways. Current tools didn’t account for various types of pedestrians and the terrain they confronted on a daily basis. What if there were barriers blocking the sidewalk? A steep incline listing to and fro? Stairs but no ramp?

“Map applications make very specific assumptions about the fact that if there’s a road built there, you can walk it,” Caspi said. “They’ll just give you a time estimate that’s a little bit lower than the car and call it done.”

But Caspi was just beginning. Artificial intelligence could only do so much. These tools were powerful, sure, but treated people as “slowly moving cars.” They lacked perspective, something with resolve and purpose, a cleareyed intent. Something, perhaps, more human.

Nearly a decade later, Caspi’s quest continues. As the director of the Taskar Center for Accessible Technology (TCAT), and lead PI of the Transportation Data Equity Initiative, she spearheads an initiative that seeks to make cities smarter and safer for everyone. About one out of every six people worldwide experiences a significant disability, according to the World Health Organization, and many encounter spaces designed without them in mind.

“Which is unacceptable given that we now have the ability to convey real information,” she said. “It’s just about the political will to make these changes.”

TCAT has filled in those gaps and more. Several of its projects have gone from print to pavement to public initiative. For instance, AccessMap, an app providing accessible pedestrian route information customized to the user, garnered a large yet unanticipated fan base shortly after its release in 2017: parents pushing strollers.

Though originally designed for those with disabilities in mind, AccessMap quickly gained a following with groups whose transportation needs ran the gamut.

“I’m focused on accessibility,” Caspi said. “But as soon as we started putting this data out, it was clear that there were many other stakeholders who were interested.”

Besides those with tykes in tow, first responders also expressed their interest after seeing the app’s potential for helping negotiate tricky areas surrounding search and rescue — or moving a stretcher to a patient. City planners saw the app’s utility for helping coordinate construction, assessing walkability and transportation planning efforts.

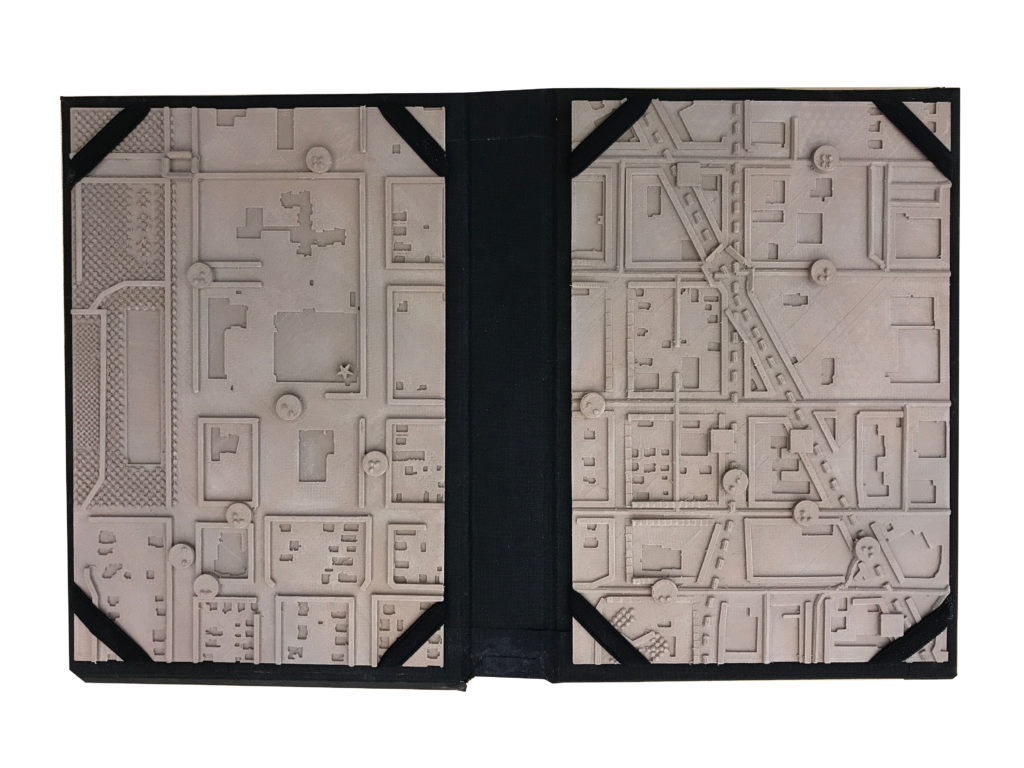

The tactile graphic representation of the OpenSidewalks data specification. The tactile map presents an alternative approach to understanding the pedestrian experience, where roads are demoted, pedestrian spaces such as parks and pedestrian paths are elevated on the map, and pedestrian amenities and landmarks are shown for a particular travel purpose. Photo by TCAT

AccessMap was the first act of OpenSidewalks, TCAT’s team project that creates an ecosystem of tools including machine learning and crowdsourcing to map pedestrian pathways better, and in a standardized, consistent manner. OpenSidewalks started as a Data Science for Social Good eScience project. Now, the venture has evolved into a global effort, one with key partners such as USDOT, Microsoft and the Global Initiative for Inclusive Information and Communication Technologies (G3ict). The USDOT funding is part of a larger initiative to create public infrastructure to support multimodal accessibility-first transportation data. Sponsors for the current ongoing project include the U.S. Department of Transportation ITS4US Deployment Program. Learn more about that project here.

AI for Accessibility and Bing Maps at Microsoft also provided financial and infrastructure support for the project.

G3ict, a nonprofit with roots in the United Nations, partnered with TCAT on the shared mission of improving accessibility in cities from a transportation and mobility perspective. Prior to the partnership, G3ict had focused more on digital accessibility — procuring software to enable residents to pay utility bills online, for example.

“This was really their first time looking at the physical environment from the accessibility perspective,” Caspi said. “For us, most of our prior experience had been in the U.S., so the tools we had created before both for using model predictions and for collecting the data were U.S. specific. This really forced us to expand our thinking.”

Together, the organizations could reach further. G3ict brought in entities from municipalities around the world, providing greater access and scope to the project. TCAT, meanwhile, leveraged its expertise in mapping and data collection to take accessibility from the screen to the streets.

“We are super happy about the partnership,” Caspi said. “Without people on the ground, you really don’t have that kind of reach typically.”

In November, TCAT and G3ict won the Smart City Expo World Congress Living & Inclusion Award for their project, “AI for Inclusive Urban Sidewalks.” The project seeks to build an open AI network dedicated to improving pedestrian accessibility around the world.

TCAT has previously collaborated with 11 cities across the U.S. and is currently partnering with 10 other cities across the Americas, including São Paulo, Los Angeles, Quito, Gran Valparaiso and Santiago, with more planned for the future.

While working with the cities, Caspi has found that each has its own personality and set of challenges specific to its location. Quito, for instance, has been focused on greenery and access to nature. The team in Los Angeles has emphasized studying building footprints and how structures interact with sidewalk environments. Meanwhile, in São Paulo, officials are prioritizing more than 1.5 million square meters of sidewalk rehabilitation and reclassification, with the hope of improving safety and walkability in key areas across the city.

“We found as we built the data more, we could reach further in terms of whom this data was relevant for and how they were using it,” Caspi said. “Through efforts focused on eco-friendly cities, transportation and people being able to reach transit services, you’re supporting sustainability within those communities.”

Caspi added that the collaboration, both within TCAT and without, has been essential and has also surprised her in how it has grown and changed shape over the years. Whether working with transportation officers in local governments or on the ground with students collecting the data, she’s seen firsthand how these efforts can build upon themselves into something greater.

For instance, Ricky Zhang, a Ph.D. student in Electrical & Computer Engineering who worked on the team, uses computer vision models to take datasets of aerial satellite images, street network image tiles and sidewalk annotations to infer the layout of pedestrian routes in the transportation system. His work was crucial to the project’s success, Caspi said.

“We hope to provide a data foundation for innovations in urban accessibility,” Zhang said. “The data can be used for accessibility assessment and pedestrian path network graph comparison at various scales.”

Eric Yeh developed the mobile version of the AccessMap web app while working with TCAT as an Allen School undergraduate. He saw the app’s potential for good, how routes in life or the everyday could branch out for the better.

“I originally joined TCAT because I was new to computer science,” said Yeh, now a master’s student studying computer science at the Allen School. “I wanted to gain programming experience while contributing to a project that would be meaningful to the community.”

The app lends itself to collaboration. Users can report sidewalk segments that are incorrectly labeled or are inaccessible, Yeh said, allowing for evolution and up-to-date accuracy. The team hopes to funnel these reports into a pipeline that automates the process.

It’s all part of a larger plan. Caspi outlined current work, including taking OpenSidewalks to a national data specification like GTFS to provide a consistent graph representation of pedestrians’ travel environments; democratization of data collection; improved tooling for data producers; and API’s that facilitate consuming the data at scale, all while limiting subjective assessments of what is considered accessible. At the same time, the Taskar Center is also pursuing non-technical tools like toolkits and workshop supports for transportation planners to discuss disability justice in their organizations and utilize community-based participatory design in trip planning and accessibility-first data stewardship. The center is also working with advocacy groups and communities to assess their accessibility and hold officials to account through a clear understanding of what the infrastructure does and does not support regarding accessibility.

For Caspi, it’s been a humbling experience to see how far the project has come, and how much work there is left to do. She sees the Taskar Center as part of a greater effort in building a sense of community, wherever one might be in the world.

“These kinds of projects can bring people together to have a better mutual understanding,” she said. “What does it take to run a city? It’s hard, right? So much from the municipal side is trying to understand storytelling and the lived experience of people through the city. Efforts like these can soften the edges around where cities meet their people. To me, that’s been really instructive.”

Read more about UW’s work on sidewalk equity here, and about AccessMap here.

Learn more about the Taskar Center’s work at the upcoming Open the Paths 2023: An Open Data & Transportation Equity Conference. Running from April 21 to April 22, the conference seeks to foster a meaningful conversation among stakeholders about mobility equity and the ways in which it can be enhanced through open, multimodal, accessibility-focused transportation data. It is free for all students and those interested can register here.