University of Washington professor Shwetak Patel has been named the recipient of the 2018 ACM Prize in Computing from the Association for Computing Machinery. Patel, who holds a joint appointment in the Paul G. Allen School and the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and also leads a team at Google, is being honored by the ACM for “contributions to creative and practical sensing systems for sustainability and health.” The ACM Prize in Computing recognizes early or mid-career computer scientists whose research has had fundamental impact and broad implications and is among the highest honors bestowed in computer science — second only to the A. M. Turing Award, which is widely regarded as the “Nobel Prize of computing.”

“Despite the fact that he is only 37, Shwetak Patel has been significantly impacting the field of ubiquitous computing for nearly two decades,” ACM President Cherri M. Pancake said in a press release. “His work has ushered in new possibilities in many applications of ubiquitous computing for sustainability and health.”

Patel began his research career as an undergraduate at Georgia Tech, where he had the opportunity to work on the “Aware Home,” a project that aimed to envision the connected home of the future. The experience inspired Patel to focus his career on developing low-power sensing capabilities that transformed how we view technologies old and new — from the humble U-bend under your sink, to the basic electrical wiring in your home, to the latest smart devices. Even as an undergraduate, Patel knew that he wanted to make his mark as a faculty member in academia, where he would have the freedom to pursue his research interests without the constraints of working in industry. Only later would he discover the extent to which he could combine the two to great effect.

“Academic life is my intellectual playground,” Patel said. “Computing has so much potential to have a positive impact on society and I’ve been fortunate to be able to try new things through my research. I’m also passionate about getting the technology out there by working closely with industry and through commercialization.”

The first industry Patel helped build was whole-home sensing for sustainability. Patel, whose work on the Aware Home led him to become a plumber and electrician in addition to a computer scientist, recognized that home systems such as the electrical wiring and plumbing could reveal fine grained information about power and water usage — so fine-grained, in fact, that he and his students figured out how to combine signal processing and machine learning to measure electricity usage at the individual device level, including televisions, lights, dishwashers, and more.

Patel and his students noted that each device places distinct “noise” on the home’s electrical system. This noise makes it possible to determine which device is in use and how much power is being consumed. Patel and his students applied a similar principle to monitor the home plumbing system by measuring pressure waves in the home’s plumbing as each faucet or fixture is turned on and off. “Your noise is our signal,” Patel would often say about this work.

Beyond the significance of the research findings, Patel demonstrated that sustainability sensing could be practical, too. His system required only a single device to be plugged into an outlet or connected to the plumbing in order to gather data on the entire system. Patel co-founded a startup company, Zensi, to commercialize this work — the first of several startups he would establish to push his research out into the marketplace. Zensi was subsequently acquired by Belkin, which opted to open its new WeMo Labs in Seattle with Patel serving as Chief Scientist in addition to his faculty position at UW.

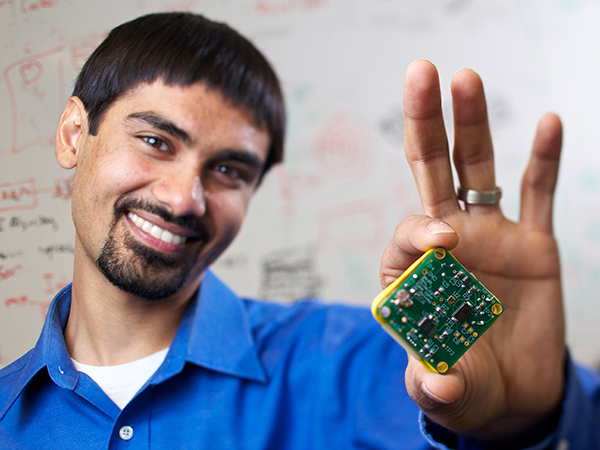

As it turned out, Patel discovered that a home’s electrical system could be used to reveal a lot more than whether someone left the television on. That same system could be used like a whole-home antenna to transmit a variety of other data points that could provide an early indication of home hazards, such as elevated moisture levels inside the walls that indicate an appliance malfunction or leak. Patel and his collaborators developed a platform known as Sensor Nodes Utilizing Powerline Infrastructure, or SNUPI for short, that leveraged a network of ultra-low-power sensors deployed throughout the home to wirelessly transmit data, via the electrical circuit, to a base station.

“Sensors can collect information in real time, enabling a homeowner to get ahead of an issue. But if you put sensors throughout the home, you don’t want to have to keep replacing batteries,” Patel noted. “Our home monitoring sensors were designed to be embedded into the wall and last for decades — essentially enabling people to ‘set it and forget it.’”

As before, Patel co-founded a company, the aptly-named SNUPI Technologies, to commercialize the team’s results. SNUPI released a consumer product, WallyHome, that was later acquired by Sears.

By that time, Patel had already begun turning his focus from sensor systems covering an entire building to ones that fit into the palm of a hand. “I began noticing how people are constantly interacting with their phones, which contain increasingly sophisticated sensing capabilities through their cameras, microphones, accelerometers, and other features,” Patel recalled. “And I started wondering how we could use these touch points to monitor health and get ahead of conditions that would otherwise require more time-consuming, potentially invasive interactions.”

One of the first projects he worked on was designed to turn a mobile phone into a handheld spirometry device for measuring lung function. SpiroSmart and a related tool, SpiroCall, enabled people to use their phones to measure their lung function at home or on the go by simply blowing into the microphone. Patel and his students demonstrated that their tool, which like the home sensing systems combined signal processing with machine learning, could achieve acceptable medical standards for accuracy compared to commercial spirometry devices — without the time and expense of an in-person doctor’s visit. They also made use of the built-in camera to develop a series of apps to screen for a variety of medical conditions, including BiliCam for detecting infant jaundice; BiliScreen for detecting adult jaundice (known to be an early symptom of pancreatic cancer); and HemaApp for measuring hemoglobin levels in the blood to detect anemia and other conditions. And these are just a few examples of what Patel has been working on. He also commercialized some of these technologies, which were acquired by Google where he now leads a team.

“That device in your pocket or hands has so much potential, and we’ve only just begun to tap into what it can do for individuals and communities,” observed Patel. “I’ve begun thinking about mobile technologies in the context of not just domestic health, but global health. What can this technology do for communities where no landline infrastructure exists, or where a significant percentage of the population is illiterate? Mobile phones are the most ubiquitous computing platform in the world.”

Patel has begun to see the opportunity in action in collaboration working with local communities and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He and his team have deployed SpiroSmart and SpiroCall in clinics in India and Bangladesh, for example, while another tool developed in his lab, CoughSense, is being used to track the spread of tuberculosis in South Africa. Meanwhile, providers in Peru are using HemaApp as a non-invasive alternative to traditional blood tests to screen children for anemia. Patel is hopeful that these and other tools will soon be available to health care providers, government and non-profit agencies, and individual users across the globe.

Academia may be his playground — a place where he can test off-the wall ideas and collaborate with students and peers to push the boundaries of what technology can do — but Patel acknowledges that it’s his forays into industry that have enabled him to realize the impact of his research at scale. The time spent working on his startups has also made him a better researcher, he says, by broadening his view of what questions he could address through his work.

“Being an entrepreneur has helped me to identify research problems I wouldn’t have previously considered solely as an academic,” Patel explained. “That experience opened up opportunities for me to venture down research paths I wouldn’t have otherwise thought about.”

Along the way, Patel has picked up numerous awards and accolades for his work, including a TR-35 Award from MIT Technology Review in 2009, a MacArthur Fellowship — also known as the “Genius Grant” — in 2011, and a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) in 2016. That same year, he was named a Fellow of the ACM, one of the highest professional honors accorded to computer scientists and computer engineers.

“Shwetak is an exceptional innovator who combines an insatiable curiosity with an unrelenting drive to produce research that has real-world impact,” said Hank Levy, Director of the Allen School. “Thanks to his technical excellence, breadth, and vision, we can now do things with sensors and smartphones that were unthinkable outside the confines of science fiction only a short time ago. Shwetak not only has expanded our understanding of what technology can do, but also created new companies and given rise to entirely new industries. And he has undertaken this amazing work all while staying true to our mission as educators and mentors of the next generation of computer scientists. I cannot think of anyone more deserving of this honor.”

This marks the first time a UW faculty member has received the ACM Prize in Computing, but not the first with a UW connection. Previous winners include Allen School alumni Jeff Dean (Ph.D., ‘96), a senior fellow at Google, and Stefan Savage (Ph.D., ‘02), a faculty member at the University of California, San Diego. The ACM Prize comes with a cash award of $250,000 from an endowment furnished by Infosys. Patel will be formally honored at the ACM’s annual awards banquet coming up on June 15th in San Francisco, California.

“I’m honored and humbled to be recognized by the ACM and my peers in this way,” Patel said. “My hope is that this award and the body of work it represents will inspire students to think broadly about the impact that they can have as computer scientists on people’s everyday lives and in the quest for solutions to our greatest public challenges. I would also like to acknowledge my hard working students whose dedication and passion really enabled all of this.”

Read the ACM announcement here and the full award citation here. See related announcements by UW News and UW ECE, and articles in GeekWire and the Puget Sound Business Journal.

To learn more about Patel’s research, visit the UbiComp Lab website here.

Congratulations, Shwetak!