At the Allen School, 22% of Fall 2025 undergraduate students are first generation, or one of the first in their family to pursue a bachelor’s degree. For first-gen students, navigating the twists and turns of higher education without a roadmap can be a daunting challenge — what are office hours? How do I choose the right courses for me? What do I do after college? Still, these students have persevered to figure it out on their own or leverage resources such as the Allen School’s first-gen student group, GEN1, to help them find their way.

In honor of the National First-Generation College Celebration on November 8, we asked students and faculty to share their experience being first and what advice they have for others still embarking on their first-gen journey. Here are some of their stories.

‘You made it here for a reason’: Kurtis Heimerl, professor

What does it mean to you and your family to be among the first to pursue a bachelor’s degree?

Kurtis Heimerl: Not much! My parents didn’t really (and still don’t really) understand higher education and the value of it. There was an expectation of increased wages (which was true!) but not really a push to attend.

How has being first-gen influenced your studies or career path?

KH: Dramatically, I think. I worked in industry at points but I think the lack of college being a “normal” path meant that I didn’t leave when it was economically sensible to do so; instead, I stayed in and got more degrees (as those credentials are things that are hard to lose once you have them). I’m not sure I’d advise my children to go all the way to a Ph.D. but the journey obviously worked for me.

What are some of the most challenging or most rewarding parts about being first-gen?

KH: There’s a lot of imposter syndrome. The reality is that you made it here for a reason. It has been rewarding being able to give back to the community that supported you; I do a lot of work for UW because it was instrumental in my own success and it’s great to see it continue doing that for new students as well.

What advice would you give to first-gen students?

KH: That the doors are open. I personally have struggled with feeling like opportunities (research, internships, etc.) weren’t for me; it seemed like others slid in so naturally to these paths, but I felt like I didn’t understand a lot of the details or nuances to succeed. The reality is that no one really understood and everyone was figuring it out.

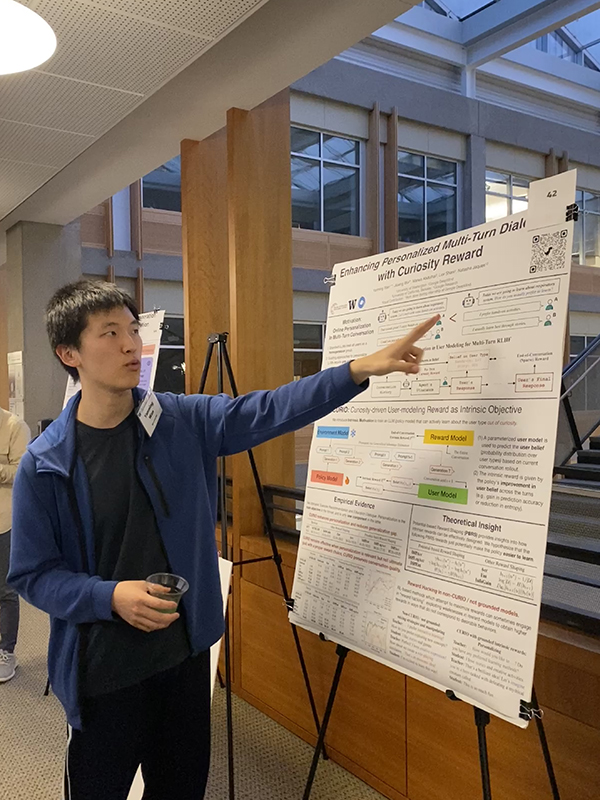

‘Your success multiplies far beyond yourself’: Sanket Gautam, master’s student, Professional Master’s Program

What does it mean to you and your family to be among the first to pursue a bachelor’s degree?

Sanket Gautam: It means breaking generational barriers and transforming not just my future, but my entire family’s trajectory. Coming from an underrepresented community in India, my degree created financial sustainability that enabled me to support others in my family to explore opportunities they never imagined possible. This achievement represents the fulfillment of countless sacrifices and dreams from those who came before me. It carries both deep pride and the profound responsibility of being a catalyst for change in my community.

How has being first-gen influenced your studies or career path?

SG: Being first-gen taught me that creating opportunity means lifting others as I climb. Without a family roadmap, I learned to seek mentors, build networks, and advocate for myself in unfamiliar environments — experiences that shaped my commitment to serving as a GEN1 mentor and participating in GEN1 coffee chats. These skills developed through navigating my own journey now drive how I approach problem-solving and collaboration in my studies and career. My pursuit of AI specialization reflects a desire to build systems that expand access and empower underrepresented communities to thrive.

What are some of the most challenging or most rewarding parts about being first-gen?

SG: The challenge is navigating uncharted territory — creating your own path when there’s no family blueprint for financial aid, career planning, or institutional processes. You become your own guide, figuring out everything from networking strategies to academic decisions through trial, error, and determination. Yet this challenge builds incredible resilience and problem-solving skills that become your greatest assets. The reward is knowing your success multiplies far beyond yourself, opening doors and inspiring others in your family and community to pursue their own dreams.

What advice would you give to first-gen students?

SG: Your unique perspective is your strength — embrace it with confidence and pride. Seek out mentors, build community with fellow first-gen students, and never hesitate to ask questions, even when it feels intimidating. The path may feel uncertain at times, but every challenge you overcome builds the resilience that will carry you through future obstacles. Remember that by forging your own path, you’re not just succeeding for yourself — you’re creating a roadmap for everyone who comes after you.

‘You get to define your own path’: Czarin Dela Cruz, undergraduate student

What does it mean to you and your family to be among the first to pursue a bachelor’s degree?

Czarin Dela Cruz: Being among the first in my family to pursue a bachelor’s degree means making the most of the opportunities my family and I worked hard for after moving from the Philippines. Having access to more resources here motivates me to push forward and make my parents proud. It’s a way to honor their sacrifices and show that their efforts were worth it.

How has being first-gen influenced your studies or career path?

CD: Being first-gen has encouraged me to stand up for myself and always look toward the future. It’s motivated me to work hard in my studies and constantly find ways to improve. More importantly, it’s inspired me to pursue my passions not just for myself, but to honor the people who supported me and made it possible for me to be here.

What are some of the most challenging or most rewarding parts about being first-gen?

CD: One of the most challenging parts of being first-gen is navigating everything on your own — from understanding college systems to balancing academics and family expectations. But it’s also incredibly rewarding to see that your hard work pays off. Being first-gen means you get to define your own path, make your own choices, and work toward your goals for a brighter future.

What advice would you give to first-gen students?

CD: My advice to first-gen students is to never be afraid to ask for help. Communicate with those around you and reach out when you need support. There are so many people and resources ready to help you succeed. Being proactive opens doors to new opportunities, and you never know what meaningful connections or experiences you might discover.

Learn more about the University of Washington’s National First-Generation College Celebration here and resources available through GEN1 here. Read more →