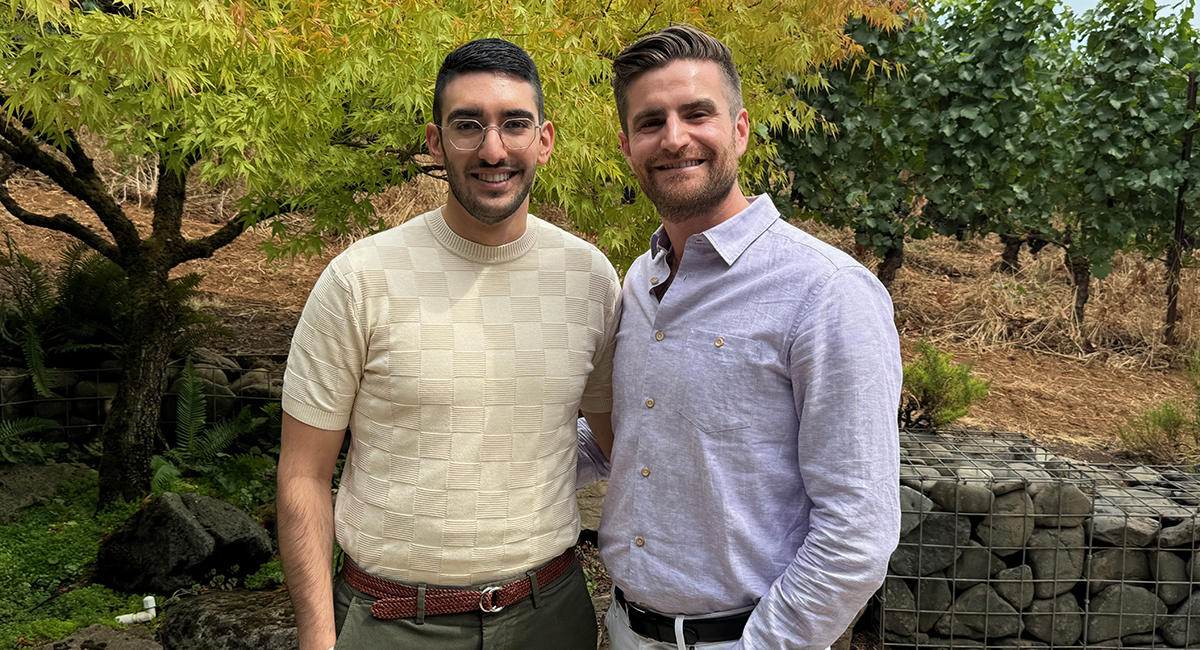

Since graduating from the Allen School, Nicki Dell (Ph.D., ‘15) has focused on using technology to “make our computing-mediated world safer and more equitable for everyone.” Her work combines the fields of human-computer interaction (HCI) and computer security and privacy to improve the lives of overlooked communities, specifically those experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) and home health care workers.

For her contributions, the Allen School recognized Dell with the 2025 Alumni Impact Award, honoring former students with exceptional records of achievement.

“This award is incredibly meaningful,” Dell said. “Whether developing mobile health tools in low-resource settings or building interventions to protect survivors of intimate partner violence from technology-facilitated harm, I learned at UW that impact isn’t just measured in lines of code or papers published — but in trust earned, dignity upheld and lives made a little better.”

During her time at the Allen School, Dell worked with the late professor Gaetano Borriello and professors Richard Anderson and Linda Shapiro on research that addresses the needs of those in low-resource settings. Growing up in Zimbabwe, she saw how limited resources and poor infrastructure created daily challenges. Dell designed a system that integrates Open Data Kit Scan, a mobile app that digitizes data from paper forms, into the community health worker supply chain in Mozambique. In her dissertation, Dell developed a mobile camera-based system to help improve data collection and disease diagnosis in low-resource environments. After graduating as the Allen School’s 500th Ph.D. student, Dell became a faculty member at the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech and Cornell University’s Department of Information Science.

“My time at the University of Washington was transformative,” Dell said. “When I began my Ph.D. journey, I never imagined the path it would lead me on — not just through the world of academic research, but into the lives and stories of people who are too often overlooked by the tech industry.”

At Cornell Tech, one line of Dell’s research has focused on mitigating technology-facilitated abuse experienced by survivors of IPV. She found that abusers threaten, harass, intimidate and monitor victims using adversarial authentication techniques to compromise victims’ accounts or devices. Dell and her collaborators also analyzed more than 500 posts in public online forums where potential perpetrators discussed strategies and justification for surveilling their partners. Building off of her research, Dell co-founded the Clinic to End Tech Abuse (CETA). Trained CETA volunteers work directly with survivors of IPV to mitigate any technology-related abuse they are experiencing, such as checking devices for spyware and providing other privacy and safety information and guidance. Her work has informed legislation, including the Safe Connections Act of 2022, upholding survivors’ requests to have themselves or those in their care removed from abusers’ shared phone plans while retaining their phone numbers. Over the years, her work has received eight paper awards and the 2019 Advocate of New York City Award.

Another line of Dell’s research investigates how technology can support home health care workers, who are some of the most under-resourced among the medical workforce. As the director of technological innovation at the Initiative on Home Care Work in the Center for Applied Research on Work (CAROW), she co-leads a multidisciplinary team of scientists, scholars and physicians aiming to improve patient outcomes and working conditions for home health care workers. For example, Dell and her collaborators designed interactive voice assistants, similar to Amazon’s Alexa, that can help home health aides manage day-to-day tasks or give guidance during medical assessments such as monitoring for leg swelling associated with heart failure. She also explored how computer-mediated peer support groups can benefit home health care workers, as well as how technology can help account for all the invisible, or unnoticed, work that these aides do for patients.

In addition to receiving this year’s Alumni Impact Award, Dell was awarded a 2024 MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, also known as the “genius grant.” Her work has also earned her the 2023 SIGCHI Societal Impact Award and a 2018 National Science Foundation CAREER Award.

“I’m immensely grateful for the mentors who challenged and guided me, chiefly among them Gaetano Borriello, whose guidance I carry with me and who is still profoundly missed,” Dell said. “I’m also grateful for the peers who inspired and encouraged me, for the broader Allen School community that cultivated in me both a rigorous technical foundation and a deep sense of purpose and for the communities I’ve had the privilege to work alongside.”

Dell will be formally honored at the 2025 Allen School graduation celebration on June 13. Read more about the Alumni Impact Award.