Allen School professor emeritus Richard Ladner, a leading researcher in accessible technology and a leading voice for expanding access to computer science for students with disabilities, has been named the 2020 recipient of the Public Service Award for an individual from the National Science Board (NSB). Each year, the NSB recognizes groups and individuals who have made significant contributions to the public’s understanding of science and engineering. In recognizing Ladner, the board cited his exemplary science communication, diversity advocacy, and well-earned reputation as the “conscience of computing.”

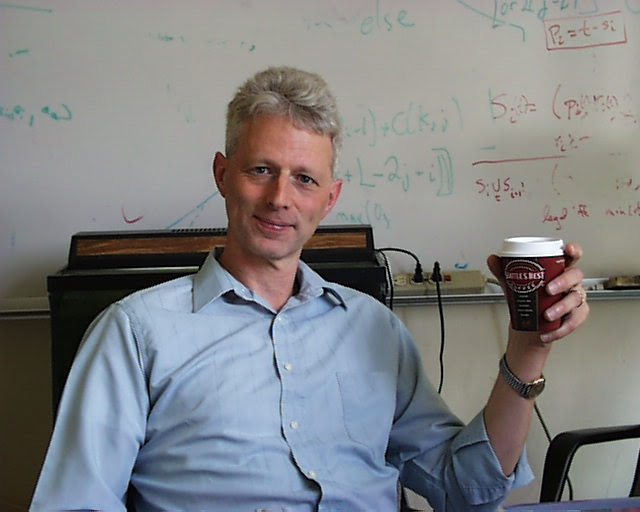

A mathematician by training, Ladner joined the University of Washington faculty in 1971. For much of his career, he focused on fundamental problems underpinning the field of computer science as one of the founders of what is now the Allen School’s Theory of Computation research group. After making a series of significant contributions in computational complexity and optimization — and later, branching out into algorithms and distributed computing — his career would take an unexpected but not altogether surprising turn toward accessibility advocacy and research.

Ladner enrolled in an American Sign Language course at a local community college, a move that represented a “return to his roots” after growing up in a household where both parents were deaf. That experience spurred him to begin volunteering in the community with people who were deaf and blind and to occasionally write about accessibility issues.

Then, in 2002, Ladner began working with Ph.D. student Sangyun Hahn at the UW. Hahn, who is blind, related to Ladner how he was having trouble accessing the full content of his textbooks; mathematical formulas had to be read aloud to him or converted into Braille, while graphs and diagrams had to be manually traced, labeled in Braille, and printed on an embosser. His student’s frustration was the impetus for Ladner and Hahn to launch the Tactile Graphics project, which automated the conversion of textbook figures into an accessible format. Ladner followed that up with MobileASL, a collaboration with Electrical & Computer Engineering professor Eve Riskin to enable people who are deaf to communicate in American Sign Language using mobile phones. Ladner also mentored many Ph.D. students in accessibility research — among them Anna Cavender (Ph.D., ‘10), who developed technology to consolidate a teacher, display screen, sign language interpreter, and captioning on a single screen; Jeffrey Bigham (Ph.D., ‘09), who developed a web-based screen reader that can be used on any computer without the need to download any software; Information School alumnus Shaun Kane, who developed technology to make touchscreen devices accessible to people who are blind; and Shiri Azenkot (Ph.D., ‘14), who developed a Braille-based text entry system for touchscreen devices.

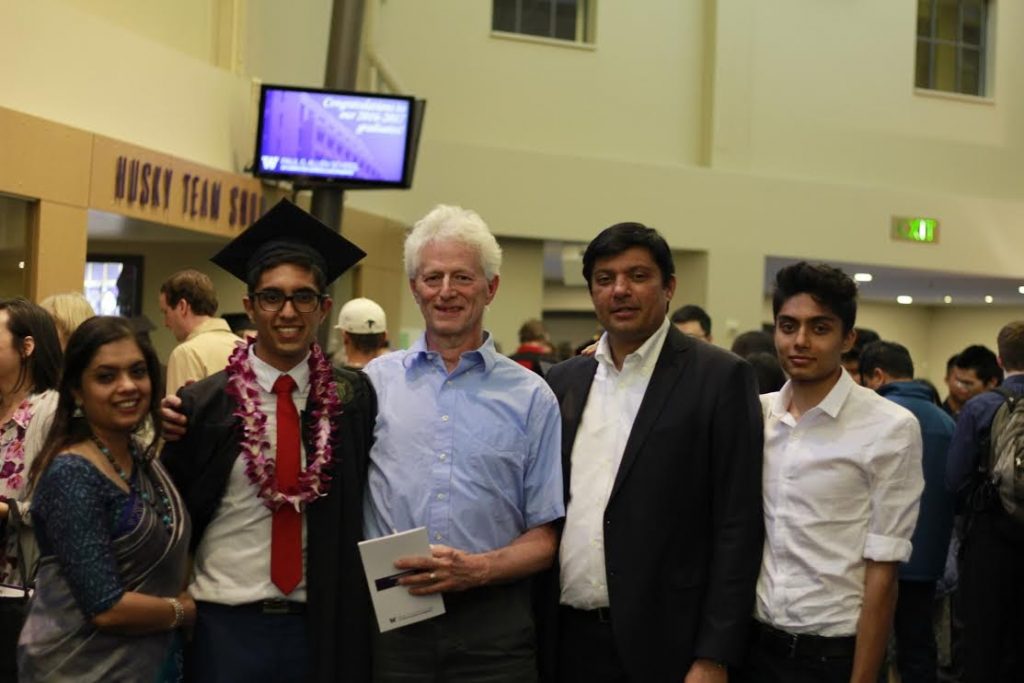

Ladner’s approach to accessibility research is driven by the recognition that to build technology that is truly useful, you have to work with the people who will use it. It’s a lesson he took from his earlier experience as a volunteer, and one that he has emphasized with every student who has worked with him since. During his career, Ladner has mentored 30 Ph.D. students and more than 100 undergraduate and Master’s students — many of whom followed his example by focusing their careers on accessible technology research.

“I visited Richard’s lab at the University of Washington just over 10 years ago. While I did get to see Richard, he was most interested in my meeting his Ph.D. students — and I could see why,” recalled Vicki Hanson, CEO of the Association for Computing Machinery. “Richard had provided an atmosphere in which his talented students could thrive. They were extremely bright, enthusiastic, and all involved in accessibility research. I spent the day talking with his students and learning about their innovative work.

“All were committed to developing technology that would overcome barriers for people with disabilities. Sometimes there are barriers in being able to use technology – in other cases, however, the use of technology actually provides opportunities to remove barriers in various aspects of daily living,” Hanson continued. “Richard’s students were working on both of these aspects of accessibility. The collegial and inspiring interactions among his students would serve as a model of research collaboration for computing labs everywhere.”

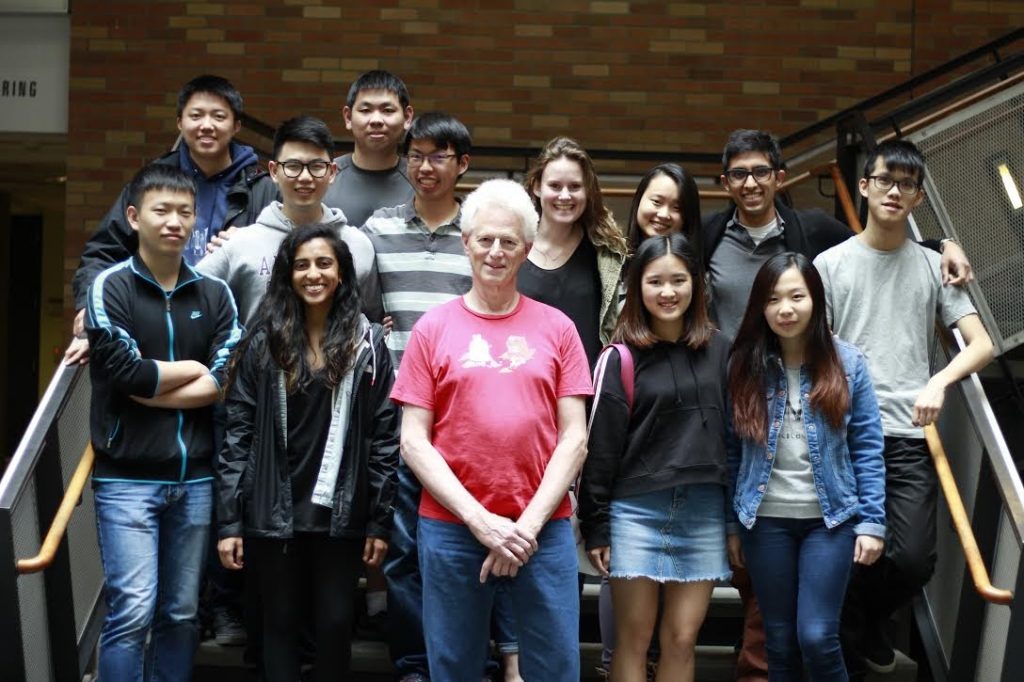

Ladner’s impact on students extends far beyond the members of his own lab. In addition to his research contributions and mentorship, Ladner has been a prominent advocate for providing pathways into computer science for students with disabilities. To that end, he has been a driving force behind multiple initiatives designed to engage a population that, until recently, was often overlooked in technology circles.

“When we think about diversity, we must include disability as part of that,” Ladner noted. “The conversation about diversity should always include disability.”

To that end, Ladner has been a leading voice for the inclusion of people with disabilities in conversations around improving diversity in technology. He served as a founding member of the board of the national Center for Minorities and People with Disabilities in Information Technology (CMD-IT). The organization hosts the ACM Richard Tapia Celebration of Diversity in Computing, which attracts an estimated 1,500 attendees of diverse backgrounds and abilities each year. Ladner was also a member of the steering committee that established the Computing Research Association’s Grad Cohort Workshop for Underrepresented Minorities and Persons with Disabilities (URMD) for beginning graduate students. In discussions leading up to the program’s launch, Ladner was instrumental in making sure that the “D” made it into the name and scope of the workshop.

Ladner has also worked directly with colleagues and students around the country to advance diversity in the field. The longest-running of these initiatives is the Alliance for Access to Computing Careers (AccessComputing), which he co-founded with Sheryl Burghstahler, Director of the UW’s DO-IT Center, with funding from National Science Foundation’s Broadening Participation in Computing program. AccessComputing and its 60 partner institutions and organizations support students with disabilities to successfully pursue higher education and connect with career opportunities in computing fields. Since its inception in 2006, that initiative has served nearly 1,000 high school and college students across the country. For seven consecutive years, Ladner also organized the annual Summer Academy for Advancing Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Computing to prepare students to succeed in computing majors and careers.

More recently, Ladner partnered with Andreas Stefik, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, on AccessCSForAll. That initiative is focused on developing accessible K-12 curricula for computer science education along with professional development for teachers. The duo also partnered with Code.org to review and modify the Computer Science Principles Advanced Placement course to ensure that online and offline course activities met accessibility standards for students with disabilities. This included developing accessible alternatives to visually-based unplugged activities as well as making interactive tools that would work with screen readers. Ladner and his collaborators on the project earned a Best Paper Award at last year’s conference of the ACM’s Special Interest Group on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE 2019) for their efforts.

This past spring, Ladner was one of nine researchers to co-found the new Center for Research and Education on Accessible Technology and Experiences (CREATE) at the UW. The mission of CREATE is to make technology accessible and to make the world accessible through technology. The center, which was established with an inaugural $2.5 million investment from Microsoft, consolidates the efforts of faculty from the Allen School, Information School, and departments of Human Centered Design & Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, and Rehabilitation Medicine who work on various aspects of accessibility.

“Richard is a gifted scientist and mentor who really helped to put UW on the map when it comes to accessible technology,” said professor Magdalena Balazinska, Director of the Allen School. “As a staunch advocate for innovation that serves all users, his impact on computing education and research cannot be overstated.”

Since his retirement in 2017, Ladner has remained engaged with the Allen School community and continues to invest his time and energy in accessible technology research and increasing opportunities for students with disabilities in computing fields. In accepting this latest accolade — one in a long line of many prestigious awards he has collected during his career — Ladner expressed optimism that accessibility’s importance is recognized by an increasing number of his peers.

“I am honored to receive this recognition from the National Science Board and heartened that the scientific community is rising to the important challenge of supporting students with disabilities,” Ladner said.

Read the NSB press release here, and learn more about Ladner’s career and contributions in a previous Allen School tribute here.