Luke Zettlemoyer, a professor in the Allen School’s Natural Language Processing group and a research director at Meta AI, was recently elected a Fellow of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) for “significant contributions to grounded semantics, semantic parsing, and representation learning for natural language processing.” Since he arrived at the University of Washington in 2010, Zettlemoyer has focused on advancing the state of the art in NLP while expanding its reach into other areas of artificial intelligence such as robotics and computer vision.

Zettlemoyer broke new ground as a Ph.D. student at MIT, where he advanced the field of semantic parsing through the application of statistical techniques to natural language problems. He and his advisor, Michael Collins, devised the first algorithm for automatically mapping natural language sentences to logical form by incorporating tractable statistical learning methods — specifically, the novel application of a log-linear model — in a combinatory categorial grammar (CCG) with integrated semantics. He followed up that work, for which he received the Best Paper Award at the Conference of Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (UAI 2005), by developing techniques for mapping natural language instructions to executable actions through reinforcement learning that rivaled the performance of supervised learning methods. Those results earned him another Best Paper Award with MIT colleagues, this time from the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2009).

After he arrived at the Allen School, Zettlemoyer continued pushing the state of the art in semantic parsing by introducing the application of weak supervision and the use of neural networks, among other innovations. For example, he worked with student Yoav Artzi (Ph.D., ‘15) on the development of the first grounded CCG semantic parser capable of jointly reasoning about meaning and context to execute natural language instructions with limited human intervention. Later, Zettlemoyer teamed up with Allen School professor Yejin Choi, postdoc Ionnas Konstas, and students Srinivasan Iyer (Ph.D., ‘19) and Mark Yatskar (Ph.D., ‘17) to introduce Neural AMR, the first successful sequence-to-sequence model for parsing and generating text via Abstract Meaning Representation, a useful technique for applications ranging from machine translation to event extraction. Previously, the use of neural network models with AMR was limited due to the expense of annotating the training data; Zettlemoyer and his co-authors solved that challenge by combining a novel pretraining approach with preprocessing of the AMR graphs to overcome sparsity in the data while reducing complexity.

Question answering is another area of NLP where Zettlemoyer has made multiple influential contributions. For example, the same year he and his co-authors presented Neural AMR at ACL 2017, Zettlemoyer and Allen School colleague Daniel Weld worked with graduate students Mandar Joshi and Eunsol Choi (Ph.D., ‘19) to introduce TriviaQA, the first large-scale reading comprehension dataset that incorporated full-sentence, organically generated questions composed independent of a specific NLP task. According to another Allen School colleague, Noah Smith, Zettlemoyer’s vision and collaborative approach are a powerful combination that has enabled him to achieve a series of firsts while steering the field in exciting new directions.

“Simply put, Luke is one of natural language processing’s great pioneers,” said Smith. “From his graduate work on semantic parsing, to a range of contributions around question answering, to his extremely impactful work on large-scale representation learning, he’s shown foresight and also the ability to execute on his big ideas and the charisma to bring others on board to help.”

One of those big ideas Smith cited — large-scale representation learning — went on to become ubiquitous in NLP research. In 2018, Zettlemoyer, students Christopher Clark (Ph.D., ‘20) and Kenton Lee (Ph.D., ‘17), and collaborators at the Allen Institute for AI (AI2) presented ELMo, which demonstrated pretraining as an effective tool for enabling a language model to acquire deep contextualized word representations that could be incorporated into existing models and fine-tuned for a range of NLP tasks. ELMo, which is short for Embeddings from Language Models, satisfied the dual challenges of modeling the complex characteristics of word use such as semantics and syntax while also capturing how such uses vary across different linguistic contexts. Zettlemoyer subsequently did some fine-tuning of his own by contributing to new and improved pretrained models such as the popular RoBERTa — with more than 6,500 citations and counting — and BART. In addition to earning a Best Paper Award at the Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL 2018), the paper describing ELMo has been cited more than 9,200 times.

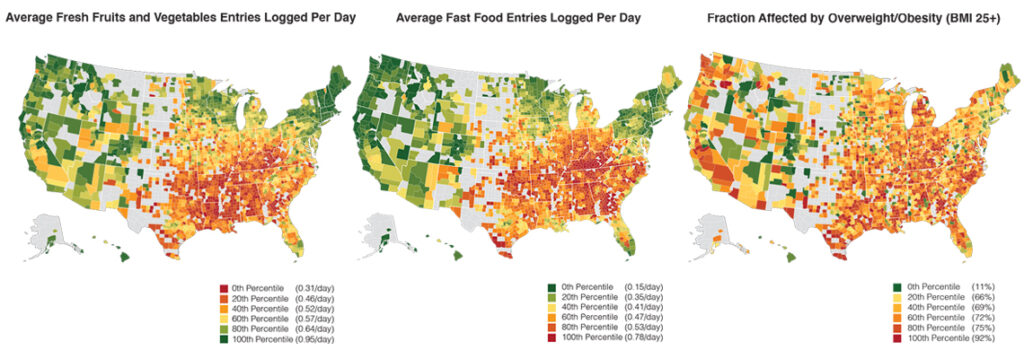

Zettlemoyer pioneered another exciting research trend when he began connecting the language and vision aspects of AI. For example, he worked with Yatskar and Allen School colleague Ali Farhadi to introduce situation recognition, which applies a linguistic framework to a classic problem in computer vision — namely, how to concisely and holistically describe the situation an image depicts. Situation recognition represented a significant leap forward from independent object or activity recognition with its ability to summarize the main activity in a scene, the actors, objects and locations involved, and the relationship among all of these elements. Zettlemoyer also contributed to some of the first work on language grounding for robotic agents, which built in part on his original contributions to semantic parsing from his graduate student days. He and a team that included Allen School professor Dieter Fox, students Cynthia Matuszek (Ph.D., ‘14) and Nicholas FitzGerald (Ph.D., ‘18), and postdoc Liefeng Bo developed an approach for joint learning of perception and language that endows robots with the ability to recognize previously unknown objects based on natural language descriptions of their physical attributes.

“It is an unexpected but much appreciated honor to be named an ACL Fellow. I am really grateful to and want to highlight all the folks whose research is being recognized, including especially all the students and research collaborators I have been fortunate enough to work with,” Zettlemoyer said. “The Allen School has been an amazing place to work for the last 10+ years. I really couldn’t imagine a better place to launch my research career, and can’t wait to see what the next 10 years — and beyond — will bring!”

Zettlemoyer previously earned a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) and was named an Allen Distinguished Investigator in addition to amassing multiple Best Paper Awards from the preeminent research conferences in NLP and adjacent fields. In addition to his faculty role at the Allen School, he joined Facebook AI Research in 2018 after spending a year as a senior research manager at the Allen Institute for AI. He is one of eight researchers named among the ACL’s 2021 class of Fellows and the third UW faculty member to have attained the honor, following the election of Smith in 2020 and Allen School adjunct faculty member Mari Ostendorf, a professor in the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, in 2018.

The designation of Fellow is reserved for ACL members who have made extraordinary contributions to the field through their scientific and technical excellence, service and educational and/or outreach activities with broad impact. Learn more about the ACL Fellows program here.

Congratulations, Luke! Read more →