Researchers in the Allen School’s Networks & Mobile Systems Lab have introduced a new kind of smart fabric imbued with computing and interaction capabilities — without the need for onboard electronics. Their work could redefine what we mean by “wearable” and usher in a fashionable new direction for computing.

Researchers in the Allen School’s Networks & Mobile Systems Lab have introduced a new kind of smart fabric imbued with computing and interaction capabilities — without the need for onboard electronics. Their work could redefine what we mean by “wearable” and usher in a fashionable new direction for computing.

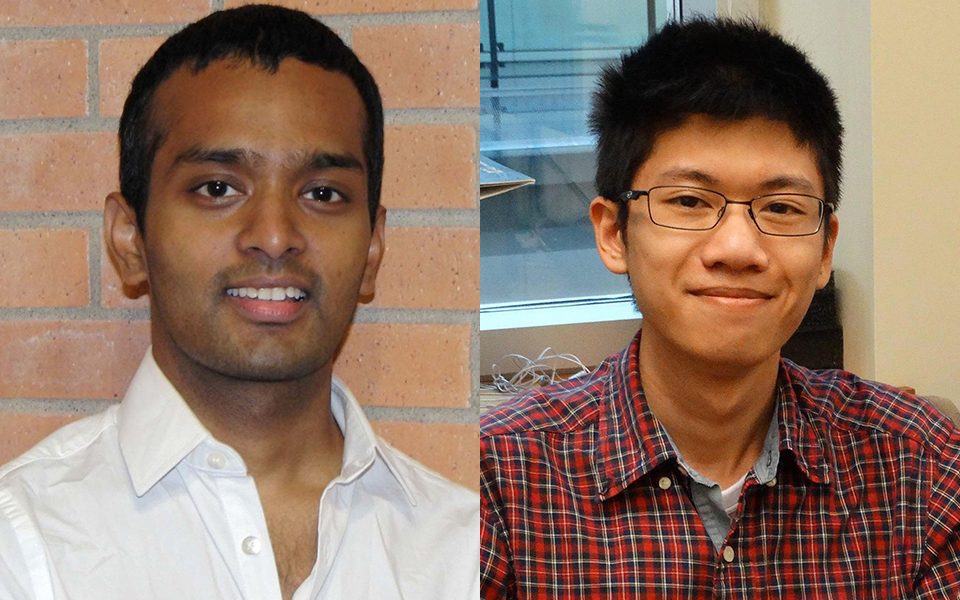

Smart garments currently on the market typically pair conductive thread with electronic components, batteries, and sensors — elements that cannot be submerged under water or subjected to extreme temperatures. Allen School Ph.D. student Justin Chan and professor Shyam Gollakota discovered that, by harnessing the magnetic properties of the same, off-the-shelf thread, they could dispense with electronics altogether and overcome one of the principal barriers to widespread adoption of wearable technology.

“This is a completely electronic-free design, which means you can iron the smart fabric or put it in the washer and dryer,” said Gollakota in a UW News release.

To produce their smart textiles, the researchers used a conventional sewing machine to embroider the conductive thread onto fabric. They then manipulated the fabric, using a magnet to align the poles in a positive or negative direction to correspond with ones and zeros. The data encoded in the fabric can be read by a magnetometer — an inexpensive device that is built into most smartphones.

Chan and Gollakota envision several potential form factors and uses for the technology, including accessories such as neckties, wristbands, and belts that can do double-duty as data storage and authentication tools.

“You can think of the fabric as a hard disk — you’re doing this data storage on the clothes you’re wearing,” Gollakota explained.

To illustrate how their smart fabric could offer an alternative to expensive RFID-based authentication systems, they sewed a magnetic patch containing an identifying image onto the sleeve of a shirt, which is then passed in front of a prototype magnetic fabric reader containing an array of magnetometers and a microprocessor. The reader determines whether the signals emitted from the sleeve match a predetermined pattern; if they do, the door is unlocked.

The team’s approach can also be used to enable gesture recognition and interaction. To demonstrate, the researchers sewed magnetized thread into the fingertips of a glove and built a gesture classifier into a smartphone. They then tested six commonly used gestures, each of which emits its own unique combination of magnetic signals, and found that the phone could interpret the signals corresponding to each gesture in real time with 90% accuracy.

“With this system, we can easily interact with smart devices without having to constantly take it out of our pockets,” said Chan, lead author of the research paper describing the team’s work.

While the magnetic signal will degrade over time — think magnetized hotel keycards that are frequently encoded and wiped as guests come and go — like those same keycards, the fabric can be re-magnetized and re-programmed over and over. Another thing the fabric and key cards have in common is their susceptibility to demagnetization in the presence of a strong external magnetic field. This is because fabric constructed with commercially available thread has a weak magnetic field, making it best suited for temporary data storage. The researchers believe that custom fabrics incorporating a stronger magnetic field could offer greater resilience for longer-term applications.

Chan and Gollakota presented their work at the Association for Computing Machinery’s User Interface Software and Technology Symposium (UIST 2017) in Quebec City, Canada last week.

Read the UW News release here, visit the project page here, and check out coverage by MIT Technology Review, GeekWire, International Business Times, Engadget, New Atlas, Quartz, The Next Web, KOMO News and KING 5 News.