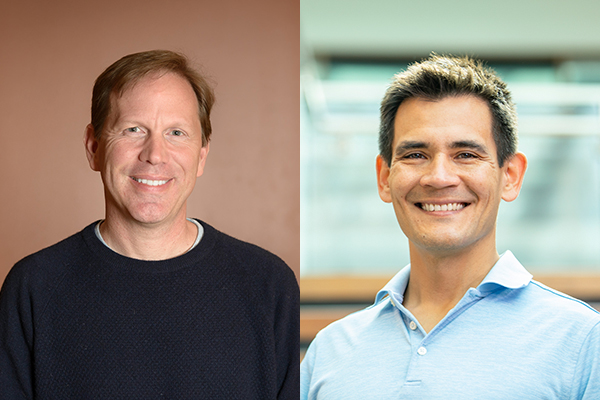

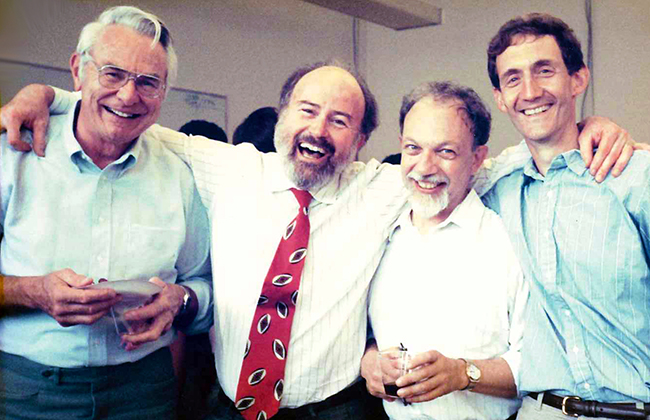

Allen School professor Luis Ceze and affiliate professor Karin Strauss, a principal research manager at Microsoft, have earned the 2020 Maurice Wilkes Award from the Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Computer Architecture (ACM SIGARCH) for “contributions to storage and retrieval of digital data in DNA.” The award, which is named in honor of the pioneering British computer scientist who built the first operational stored-program computer, recognizes an outstanding contribution by a member of the computer architecture field within the first two decades of their professional career. Ceze and Strauss are the first recipients to share the award in its 22 year history.

“The Maurice WIlkes Award has always been an individual honor, but I think the award committee made the right choice in recognizing Karin and Luis together,” said Allen School professor Hank Levy, who recruited Ceze and Strauss to the University of Washington. “We are witnessing the emergence of an entirely new area of our field — molecular information systems — and Karin and Luis are at the forefront of this exciting innovation.”

Since 2015, Ceze and Strauss have co-directed the Molecular Information Systems Laboratory (MISL), a joint effort by the University of Washington and Microsoft to explore synthetic DNA as a scalable solution for digital data storage and computation. They achieved their first breakthrough the following spring, when they described an archival storage system for converting the binary 0s and 1s of digital data into the As, Ts, Cs, and Gs of DNA molecules. The team followed up that achievement by storing a record-setting 200 megabytes of data in DNA, from the Declaration of Human Rights in more than 100 languages to the music video for “This Too Shall Pass” by popular band OK Go.

The team would later publish the science behind this feat in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Biotechnology, along with a description of their technique for achieving random access using a library of primers that they designed and validated for use in conjunction with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The latter was a crucial step in demonstrating the feasibility of a large-scale DNA-based digital storage architecture, since such a system would be cost- and time-prohibitive without building in the ability to quickly and easily find and retrieve specific data files without sequencing and decoding the entire dataset.

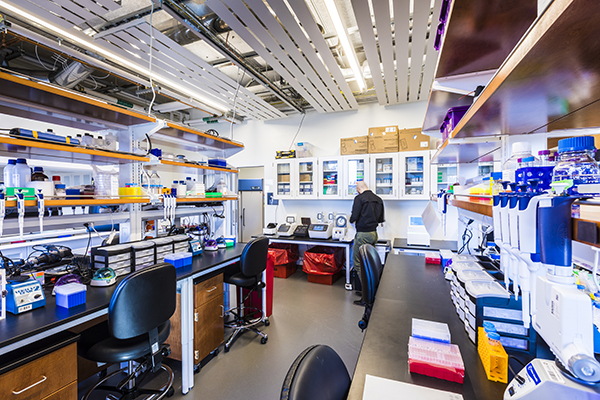

Last year, Ceze, Strauss, and their colleagues introduced the world to the first automated, end-to-end system for DNA data storage, encoding the word “hello” as five bytes of data in strands of DNA and recovering it. Their fully functioning prototype incorporated the equipment required to encode, synthesize, pool, sequence, and read back the data — all without human intervention. After demonstrating it was feasible to automate DNA data storage, they moved on to showing how it could be practical, too, unveiling a full-stack automated digital microfluidics platform to enable DNA data storage at scale. As part of this work, the lab designed a low-cost, general-purpose digital microfluidics device for holding and manipulating droplets of DNA, dubbed PurpleDrop, which functions as a “lab on a chip.” PurpleDrop can be used in conjunction with the team’s Puddle software, an application programming interface (API) for automating microfluidics that is more dynamic, expansive, and easier to use than previous techniques. Since then, the team has begun exploring new techniques for search and retrieval of data stored in DNA, such as content-based similarity search for images.

”Many people don’t envision a wet lab full of pipettes and DNA quantification, synthesis, and sequencing machines when they think of computer architecture,” Strauss admitted. “But that’s what makes this work so interesting, and frankly, thrilling. We, computer architects, get to work with an incredibly diverse group of brilliant researchers, all the way from coding theorists and programming languages, to mechanical and electrical engineering, to molecular biology and biochemistry.

“Having done this research has only energized us further to continue working with our colleagues to push the boundaries of computing by demonstrating how DNA, with its density and its durability, offers new possibilities for processing and storing the world’s information,” she concluded.

In addition to pushing the boundaries of computer architecture, Strauss, Ceze, and the other MISL members have made an effort to push the limits of the public’s imagination and engage them in their research. For example, they collaborated with Twist Bioscience — the company that supplies the synthetic DNA used in their experiments — and organizers of the Montreux Jazz Festival to preserve iconic musical performances from the festival’s history for future generations to enjoy. In 2018, the lab enabled the public to take a more active role in its research through the #MemoriesInDNA campaign, which invited people around the world to submit their photos for preservation in DNA under the tagline “What do you want to remember forever?”

More recently, the MISL team entered into a collaboration with Seattle-based artist Kate Thompson to pay tribute to another pioneering British scientist, Rosalind Franklin, who captured the first image revealing the shape of DNA. That tribute took the form of a portrait comprising hundreds of photos crowdsourced from people around the world as part of the #MemoriesInDNA campaign. The researchers encoded a selection of those photos in DNA, with redundancy, and turned the material over to Thompson. The artist then mixed it with the paint to infuse Franklin’s portrait with the very substance that she had helped reveal to the world.

“We believe there are a lot of opportunities in getting the best out of traditional electronics and combining them with the best of what molecular systems can offer, leading to hybrid molecular-electronic systems,” said Ceze. “In exploring that, we’ve combined DNA storage with the arts, with history, and with culture.”

In addition to combining science and art, Ceze has also been keen to explore the combination of DNA computing and security. In a side project to his core MISL work, he teamed up with colleagues in the MISL and in the Allen School’s Security and Privacy Research Lab to explore potential security vulnerabilities in DNA sequencing software. In a highly controlled experiment, the researchers encoded an exploit in strands of synthetic DNA. They then processed the sample with software compromised by a known vulnerability to demonstrate that it is possible to infect a computer by malicious code delivered through DNA. Ceze also worked with a subset of that same team to understand how people’s privacy and security could be compromised via online genetic genealogy services — including, potentially, the spoofing of relatives who do not exist.

“As the intersection of DNA and computing becomes more mainstream, it’s important to highlight these vulnerabilities,” Ceze explained. “We want to address any security issues before they can cause harm.”

Ceze joined the University of Washington faculty in 2007 after earning his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Early in his career, Ceze emerged as a leading proponent of approximate computing, which aims to dramatically increase efficiency without sacrificing performance. His work has blended operating systems, programming languages, and computer architecture to develop solutions that span the entire stack, from algorithms to circuits. While approximate computing most often focuses on computation itself, Ceze was keen to apply the principle to data storage. He teamed up with Strauss and other colleagues at UW and Microsoft to focus on what he calls “nature’s own perfected storage medium,” and the rest will go down in computer architecture history.

“Luis established himself as a leader in the architecture community when he took approximate computing from a niche idea to a mainstream research area,” said Josep Torrellas, Ceze’s Ph.D. advisor and director of the Center for Programmable Extreme-Scale Computing at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Since then, his contributions working alongside Karin on synthetic DNA for digital data storage have been nothing short of groundbreaking — encompassing an overall system architecture, decoding pipeline, fluidics automation, wet lab techniques and analysis, search capabilities, and more.

“Luis and Karin have advanced a completely new paradigm for computer architecture, and they did it in an impressively short period of time,” he continued. “I can’t think of anyone working in the field today who is more deserving of this recognition.”

Strauss, who also earned her Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign working with Torrellas, joined Microsoft Research in 2009 after spending nearly two years at AMD. A major focus of her work over the past decade has been on making emerging memory technologies viable for use in mainstream computing. In 2013, Strauss contributed to a paper, along with Ceze and their Allen School and MISL colleague Georg Seelig, exploring new approaches for designing DNA circuits. That work challenged the computer architecture community to begin contributing in earnest to the development of this emerging technology. She led the charge within Microsoft Research, along with Douglas Carmean, to devote a team to DNA-based storage, leading to the creation of the MISL.

“Karin is a pioneering researcher in diverse areas of research spanning hardware support for software debugging and machine learning, main memory technologies that wear out, and emerging memory and storage technologies,” said Kathryn McKinley, a researcher at Google. “Her latest research is making DNA data storage a reality, which will revolutionize storage and computing. It is heartwarming to see the amazing research partnership of Karin and Luis recognized with this extremely prestigious award.”

The Maurice Wilkes Award is among the highest honors bestowed within the computer architecture community. Recipients are formally honored at the ACM and IEEE’s Joint International Conference on Computer Architecture (ISCA). This year, the community celebrated Ceze and Strauss’ contributions in a virtual award ceremony as part of ISCA 2020 online.

“We are tremendously proud of Luis and Karin! They are true visionaries and trail-blazers and their creativity never ceases to amaze me,” said professor Magdalena Balazinska, director of the Allen School. “I look forward to seeing the next exciting research results that will come out of their lab. Their work so far has definitely been very impactful, and I’m very happy they have been recognized with this prestigious award.”

Congratulations, Karin and Luis!